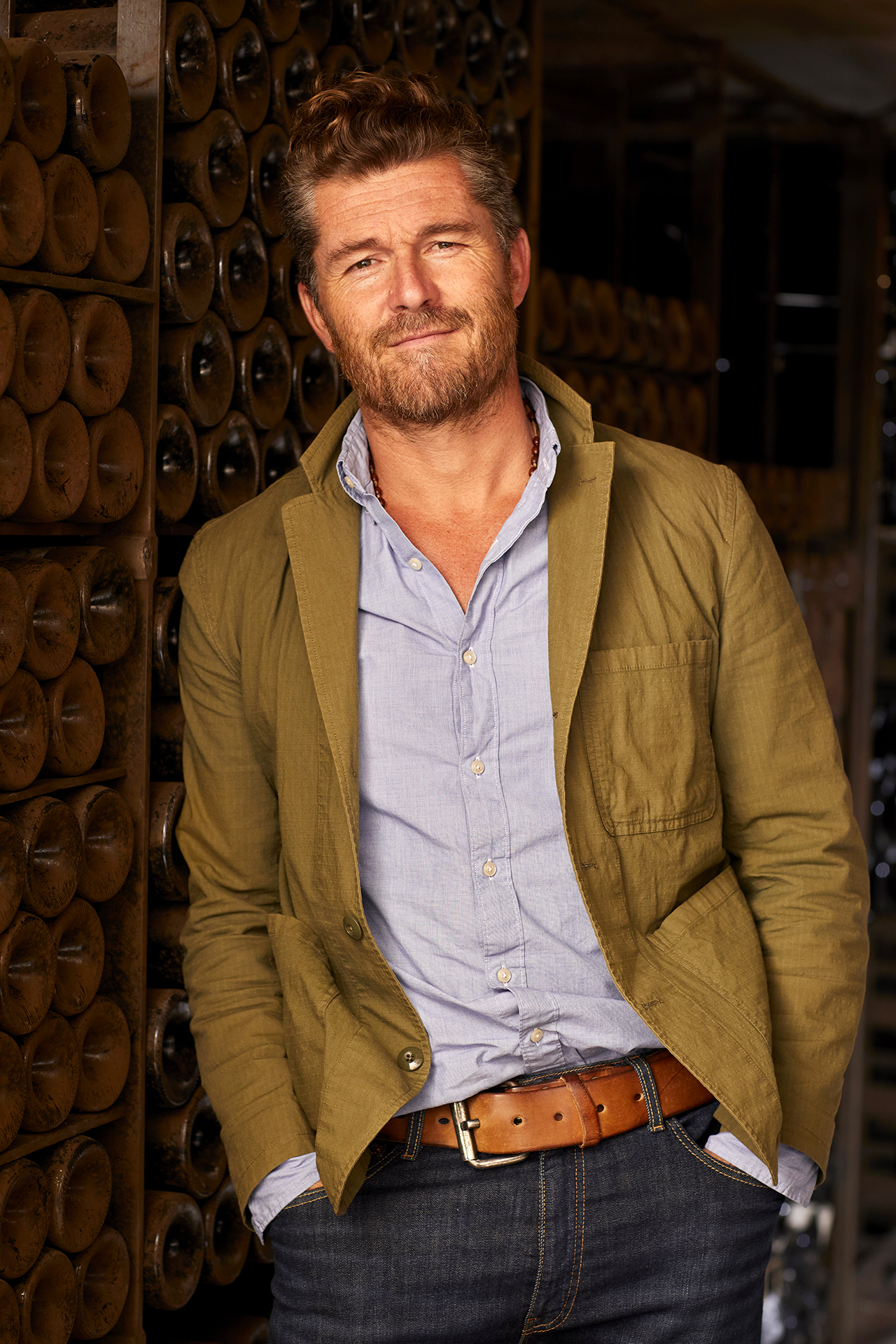

France’s 50 best winemakers: Nicolas Audebert of Vignobles Chanel

Winemaker and manager of the French luxury house’s four estates: “One foot firmly on the ground, the other up in the stars”.

The iconic haute couture house has been producing wine for almost 30 years. At the head of Bordeaux’s Château Berliquet, Château Canon, Château Rauzan-Ségla, and Provence’s Domaine de l’Île, is Managing Director and globetrotter, Nicolas Audebert, who stands at #9 in the rankings.

Appointed head of Chanel’s vineyard properties in 2014, the talented Nicolas Audebert oversees three Bordeaux estates (Châteaux Canon and Berliquet in the Saint-Émilion appellation, Château Rauzan-Ségla in the Margaux appellation), and the Île de Porquerolles estate. With his casual appearance, tousled hair, and sun-kissed complexion, he exudes a rock-star charisma that has propelled him to magazine-cover stardom. The oenologist and agronomic engineer, who honed his skills at Krug before taking charge of winemaking at Cheval des Andes in Argentina, seems to possess the Midas touch, turning everything into gold. Whether it’s a classified Bordeaux Grand Cru or a Côtes de Provence rosé, this virtuoso of the vine knows how to craft excellent wine.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Nicolas Audebert: – I’m not even sure that I am a winemaking champion! I’ve been lucky enough to work for some very prestigious names that have helped me to get to where I am today. It’s the brands, the vineyards, the terroirs, and the people I’ve worked with that have brought me to where I am, a position where people might say that I’m some kind of champion, but really I’m not. There are scores of people who are far more competent than me. I take my hat off to all the small-scale winemakers who make fantastic wines for 15 euros a bottle, that nobody knows and who are the real champions, as their job is far more difficult. When you work for a big name, with substantial resources and great terroirs, it’s a whole lot easier.

Have you been training for long?

I don’t see it as training. I do it because it’s a real vocation: my love for grape growing and winemaking is behind everything I do. If we take the example of musicians or sports stars, there are those who achieve with hard graft, and then those who take real pleasure in it, who have a passion for it. Obviously, as winemakers, we’re constantly tasting things, and we probably taste other people’s wines more often than our own, to learn and understand. I’ve been making wine now for 25 years. I didn’t grow up in the wine world. I fell into it, I won’t say by accident, but because I loved nature and wanted to do something that involved being close to the land. Wine seemed an obvious choice: it allows you to transform an agricultural product into an experience that is emotional, sensory, cultural, historical. As winemakers, we have one foot firmly on the ground and the other up in the stars!

Who is your mentor?

We learn daily from everything – and everyone – around us. Whether it’s with a renowned South American oenologist, a Champagne cellar master, a wine connoisseur – I’m constantly discovering new things. I learn from talking to enthusiasts who’ve tasted everything under the sun, I learn from talking to winemakers who’ve been in the game decades. I was lucky enough to work with Rémi and Henri Krug for many years. I also worked with Maggie Henriquez, a rather exceptional woman, and with Philippe Coulon. I worked with Roberto de la Mota, the renowned oenologist from Argentina. I worked for 10 years with Pierre Lurton; he taught me a great deal. And I continue to learn every day with our estate workers.

Is wine a team sport?

Yes, it’s definitely a team sport. First of all, it’s a long-term process. Our team exists outside time – when we take a bottle of 1929 or 1947 Château Canon from the cellar, it’s the same team which made both wines. Great wines are not bound by the limits of time – they capture the essence of a particular place, a path, a destiny. We bear the weight of all that history on our shoulders; we need to write our own part in it.

There are many people in my team: first, the people who work every morning out in the vineyards. I’m not the one out there tending to the vines, pinching them back, tying them up, turning the barrels, racking the wine. After that, we have to blend and taste, with our consultant oenologists, Éric Boissenot and Thomas Duclos, and with our in-house winemakers. Beyond that, there’s also a little bit of Roberto de la Mota and Maggie Henriquez in my Saint-Émilion wines.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

Of those two elements, only one of them is indispensable: the terroir. If you don’t have an exceptional terroir or a distinctive winemaking signature, you won’t make good wine. That said, I don’t agree with the current line of thought saying that everything needs to happen by itself. Grapes that jump of their own accord into bottles and suddenly make great wines, without anyone doing anything, simply do not exist. You need someone to work on them, so it’s a union between the team that does that work and the terroir on which the grapes are grown – a bit like a horse and its jockey. It’s the horse that does the running, the winning, that has all the mental and physical qualities needed. But it needs a rider, to say “Go that way!” and to keep its pace steady at the beginning before sprinting to the finish line. That said, the ratio isn’t necessarily the same: it’s perhaps 80% horse and 20% jockey, whereas it’s probably 70% terroir and 30% winemaker.

If there’s nobody there to care for vines, and cut them back, they don’t make grapes, they just create tendrils and exhausted fruit. Without human hands giving them enough stress and direction, they won’t give anything. And without grapes, humans can’t make wine, so it really is the meeting of both, but a meeting where the winemaker’s style must be the expression of the terroir.

To what do you owe your success?

Above all, I owe it to my parents and to the upbringing they gave me. They taught me to be demanding of myself and of those around me, but they also imbued in me a respect for other people, a sense of patience, an ability to listen, boundless energy, and a desire to achieve, which means that I perhaps have certain qualities that make people want to go along with my projects and put their trust in me.

Is your family proud of you?

Yes, my family is proud of me. That said, the word “proud” sounds rather arrogant to me, a bit egocentric. I would like to think that the life that I am lucky enough to lead today – professional, social, and cultural – is something they look up to, rather than feeling pride for me. In my eyes, words like fulfilment, balance, and desire are far more important than pride.

Who is your most important sponsor?

If we’re talking in purely professional terms, it is Chanel. It’s a wonderful couture house which gives me the freedom to do what I do because it’s an organisation that understands you have to play a long game, and because it is run by people with a huge sense of creativity, who are striving for excellence. They are a truly extraordinary sponsor.

What is your favourite colour?

The colour of the soil, as it has so many different shades. There are ochre soils, red soils, brownish-black soils, sandy soils. It’s this mosaic of colours that allows us to make our great wines and bring complexity to them.

Your favourite grape variety?

I would have to say Malbec, as I hold a particular attachment both to the grape variety and to the wonderful country that is Argentina. It’s a grape variety with quite an extraordinary history, which ended up finding somewhere to call home on the other side of the world, in the most unlikely of places. It left Cahors and came to Bordeaux, where it was planted before disappearing again and going over to South America. It was planted first in Chile, then in Argentina; it crossed the Andes by horse, in the saddlebags of President Sarmiento and a French scientist called Pouget. And then, finally, it found a place in the foothills of the Andes, on the Argentine side, high up on the Altiplano plains, in a continental climate, where it felt at home and was happy.

Your favourite wine?

Amongst the wines that we have here in our cellars and that I have been lucky enough to taste, there are a few that are truly extraordinary, that mark you for life. There are certain vintages of Rauzan and Canon that I won’t ever forget, like 1964, 1955, and 1929, for example. They are all absolutely unbelievable wines. I have memories from all over the place, whether it’s in the Piedmont, in South America, in Burgundy, in Champagne. There are exceptional wines everywhere. However, if I had to keep just one bottle, the one that made the greatest impression on me, it would be Krug 1928, which has an incredible history. Bottles of this vintage had been seized by the Germans to be sold on the British market, but the British didn’t want them because they had been disgorged for a while, and Joseph Krug was able to salvage them. Bottles of Krug 1928 are almost 100 years old, and absolutely extraordinary.

Your favourite vintage?

I wouldn’t pick one that’s too old, or one that’s too young. I would have to say 2001 because, whether it was on the Right or the Left Bank, it made for an extraordinarily precise wine. It isn’t an iconic vintage by any means, but at the same time, it shouldn’t be overlooked. It’s not a small vintage, the wines it produced are very clear, very precise, they say what they have to say without shouting it from the rooftops, but rather with humility.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

My wines have a strong identity, they are the mirror of the land from which they were born. People often say that a dog is the reflection of its owner, but a wine must take after the place from which it comes. Today, you could make a wine in Margaux that was modern, sun-drenched, Mediterranean, extracted, powerful, with exotic accents – why not? But that is not what customers are looking for. Similarly, if you’re making, somewhere deep in South America, a wine without colour, that’s austere and cold – something is wrong. Wine reflects a culture, a path, and this path was set by the land, the climate, the people, and the wine needs to resemble this, it needs to be rooted in a very specific place. Take Canon for example, which has a very specific terroir, with clay-limestone soils, on the plateau of Saint-Émilion. This is a terroir that doesn’t lie, it’s a terroir where you couldn’t be doing anything else. When tasting a wine, people often make analogies to refer to its character. They often say: “This one is slightly withdrawn, it’s a little shy, you need to give it time. It needs to grow in confidence”. Or you could have a headstrong wine, that knows what it wants to say, and says it very bluntly and directly. I wouldn’t be able to make a wine if I didn’t have a clear idea of what kind of person it would be.

What are the best circumstances in which to taste your wine?

In good company. You should never drink alone, as wine is designed to be shared, to build bonds between people.

With whom?

Some people say that you should only open good bottles with people who understand wine, but I think that’s a real shame. In my eyes, you should open those bottles with anyone who wants to drink them, whether they understand or not. The pleasure, the sense of discovery, the satisfaction, and the emotion that great wines afford are within everyone’s grasp: those who know about them and those who don’t. Obviously, you shouldn’t open a great bottle with someone who won’t enjoy it, it wouldn’t make any sense. But if the desire to open it and share it is there, even the greatest bottle can be opened with someone who doesn’t know much about wines, because these moments are about conveying emotion, about passing on this immutable knowledge that exists outside of time.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wine?

I’m lucky enough – or unlucky enough – to be on a natural high all the time. I’d almost prefer for it not to be the case! However, I would never enhance my wine with chemical assistance. There’s this trend for souped-up wines but they bear no interest for me whatsoever. It’s far more interesting when things are full of surprises, when you gradually discover different aspects that bring complexity. This complexity is the opposite of in-your-face showiness. Chemically enhancing wines allows you to achieve a feat once but, behind that, there’s nothing, because it’s part of a system that is distorted from reality, showy, and short-lived. The point of wine is for it to be always true, and precise.

Who is your worst enemy?

I’m my own enemy – if I weren’t, life would be very dull! The hardest thing is to know yourself and to understand your own strengths and weaknesses. It’s always easy to talk about our strengths. Our weaknesses are much harder to work on. In the wine world, which is a world of pleasure, of shared experiences and emotions, I don’t really see any competition or enemies.

And your greatest achievement?

My only motivation is my family and our life together. I try to pass on to my children a bit of the upbringing that I received – with its values and traditions – but also an openness and willingness to discover the world. I still have so many things to do, places to go, wines to drink, countries to discover, people to meet: it’s this desire to be open to and interested in everything and everyone that I want to pass on to them.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

It is, above all, allowing ourselves to be innovative and not being scared of asking questions or implementing new things. In some places, the wine world is defined by a multitude of traditions; in others, it is all about constant innovation. It is quite rare for the two things to coincide. In the places where it’s very traditional, if you do things a bit differently, then it’s often very marginally so, just to be able to say that you do things differently. On the other hand, there are some vineyards, some regions, that aren’t bound by tradition, and are free to innovate. In a traditional vineyard, wanting to do things differently is ultra-modern and innovative in and of itself. When I arrived in Bordeaux, I had never worked in the region before. I had no qualms about implementing new ideas or developing things that didn’t follow the traditional Bordeaux way. You need a mix of both: one eye looking ahead and one eye looking back.

Can you give me an example?

Conducting several harvests within the same plot, for example, according to the exposure of the rows, and then vinifying the grapes separately according to this. Depending on the aspect of the row, some phases get more sunlight than others in the very warm years, with grapes that will be riper, spicier, darker, and more intense than others that will be fresher, more acidic, and have more tension. It’s hard to vinify them all together while staying precise, so in certain years we do several harvests within the same plot and vinify its grapes separately. Another example is the concept of having people taste wines straight from the barrel during en primeur and for the definitive blend, letting them can pick whatever barrel they want to taste from, which allows us to talk about the wine and be completely transparent about what we have in our cellars. There is a highly distinctive approach to tasting in Bordeaux.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

Pierre Lurton. One should always pay honour where honour is due!