Winemaker of the storied family-run estate: “Passion isn’t something you can pass down”.

Our next interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series finds us in the Northern Rhône, where we meet Jean-Louis Chave, who stands at #8 in the rankings, a winemaker perpetuating not only his family’s legacy but that of an entire region.

The sixteenth generation in a long line of winemakers, Jean-Louis Chave has proven to be a worthy successor. His wines, known for their precision and purity, express all the character of the Hermitage terroir. During the 1990s, the Rhône winemaker set himself a new goal: to reinvest in the Bachasson hillside, located in Saint-Joseph, the very place where the family’s ancestors began their viticultural journey. From the start of his career, Jean-Louis Chave turned to practices of days past to tend to his vineyard. Long before receiving the certification it holds today, the estate was already employing organic methods. However, the winemaker does not want to rest on the laurels of his success, in France and around the world, but remains on a relentless quest for perfection. Through this interview, we meet with a man of remarkable humility.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Jean-Louis Chave – This achievement is thanks to the terroirs that we represent, and we strive to live up to their standards. The winemaker is entirely reliant on the terroir – there is no great winemaker without great terroir.

Have you been training for long?

For us, it’s a family affair, as I’m a sixteenth-generation winemaker. This makes me think about the question of transmission, which I’ve often thought about and continue to think about now I have children.

What are we passing down?

You can pass down a profession, and all its ways of working, but passion isn’t something you can pass down. I started working in the vines in 1992 or 1993, it’s been 30 years now. This is a long-term commitment, the practice of winemaking. An athlete will try to repeat an achievement or try to improve on it in a short amount of time, but us winemakers, we need to wait a cycle, an entire year, to express ourselves again. Rather than speaking of training, I prefer to think of it in terms of interpreting the terroir. To really achieve this, you must understand it, and this takes time.

Who is your mentor?

My father, definitely. But also, the wine enthusiasts who follow our approach, to whom we have a sense of responsibility, a duty of excellence.

Is wine a team sport?

Yes, especially in our region, where the vineyards are planted on steep slopes, and are cultivated the same way my ancestors cultivated them, without any machinery. We think of ourselves as “gardener-winemakers”. You need one and a half people per hectare of vines, whereas, in other regions, one person can easily cover 12 to 15 hectares.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the team?

What counts is the terroir. The winemaker is just an interpreter. They mustn’t damage what Nature has given them; they are there to accompany the terroir to its fullest expression, which is the wine they will make from it.

To what do you owe your success?

To our good fortune in having certain terroirs that have been in our family for a very long time. We also owe it to our philosophy of a job well done, and to our craftsmanship that has developed over the years, always driven by the idea of continuous improvement.

Is your father proud of you? And your children?

With my father, I think the pride goes both ways, the satisfaction of seeing the story continue to unfold. As for my children, I don’t want to force them to be part of our story, of our profession. It needs to come from them. That’s another philosophy we’ve always embraced: that our story, no matter how long, can end, or transform itself. The Hermitage was here before us, and whatever happens, it will be here long after us.

Who has been your biggest sponsor throughout your career?

The world of wine enthusiasts, the people who encourage us in our work. Wine exists when it is enjoyed, when it conveys an emotion, a reaction. These emotions, these reactions, they encourage us to keep telling our story. Restaurateurs also play a very important role because they give life to our wines.

Your favourite colour?

The gradient of greens you find in the natural world, and the blue of the sky. As for wines, you can’t separate what you drink from what you eat, so the colour is going to depend on the dish. Ideally, you would pick a wine and adapt the dish to it. Unfortunately, we are living in a time where chefs receive a lot of media attention, which means wine often plays second fiddle.

Your favourite variety?

Our form of expression is Syrah for the reds, Marsanne and Rousanne for the whites. I can’t say I prefer Syrah to Marsanne, it’s like being asked to pick your favourite child. The variety matters little, what really matters is the terroir. The variety is the prism through which the terroir is expressed.

Your favourite cuvée?

Historically, at the estate, our favourite cuvées have been Hermitage wines. It’s my generation’s mission to give a certain importance to another appellation which is hard to define, but very captivating: Saint-Joseph. We are trying to raise the bar.

Your three favourite vintages?

I would say 1991, a vintage that has fully matured, and that embodies what a great wine of Hermitage should be.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

I would want it to be someone who resembles the terroir it hails from. When you make a wine, you think of its hills, of its landscapes. What I want is for people, when they taste our wine, to recognise a piece of its birthplace. For those who don’t know our terroirs, I hope they find the harmony, the softness, the strength, and the colours that characterise the great wines of Hermitage.

What’s the best way to enjoy it?

The best way to discover our wine is always with food, whether it’s at a restaurant, or sitting around a table at home.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing your estate?

What is chemical enhancement? Adding a bit of sugar, a bit of tartaric acid, the tannins brought by oak? What counts, is remaining true to yourself, and true to the wine. Wine must be natural, not in the sense that it’s free from additives, but in the sense that it must be true, sincere. It takes work, despite all this, to ensure wine is its truest expression, in relation to its origins and to what it should be. You can’t take a hands-off, laissez-faire approach, because without any intervention, wine would be vinegar! It’s a fine line: you must stay close to the purest of truths, but that isn’t going to happen automatically. At the estate, everything is organised so we can do as little as possible, but we sometimes need to accompany the wine so it can express itself fully.

For what price would you be prepared to sell your estate?

Everything is meant for the estate to remain in the family, but should that not be the case, we will probably sell, and this sale will be its own kind of transmission. It won’t be a question of price, because the most important question is knowing who will be taking on the estate and turning a new leaf in its story.

What is your greatest achievement?

The vine-covered slopes of Saint-Joseph, including one that belonged to my family from 1481 until the phylloxera epidemic in 1880. My ancestors worked on those steep slopes for almost 400 years and were forced to abandon them without really understanding what was happening. I’m proud of having been able to replant them, over 100 years later. They are located close to a town called Bachasson, next to a place known as Chave. I started this long-term project in 1995, and the last vines were replanted in 2007.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

My most innovative strategy has been working just as they did back in the day. When I first started, people would tell me: “You work like they did in the olden days.” At the time, what was groundbreaking was knowing all the names of the chemical molecules, or working with chemistry, whereas now, if you’re working with chemistry you’re stuck in the olden days! I’ve been interested in biodynamics for 15 years. I had counterparts and friends in other regions that followed biodynamic principles – Aubert de Villaine (previously co-manager of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, ed.) for example. I can’t explain why, but I feel like this method works.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

There is no hierarchy: it could be a young, passionate winemaker who does their job right, with a bright future. Every winemaker who does their job right deserves all the recognition they get.

Winemaker and manager of the French luxury house’s four estates: “One foot firmly on the ground, the other up in the stars”.

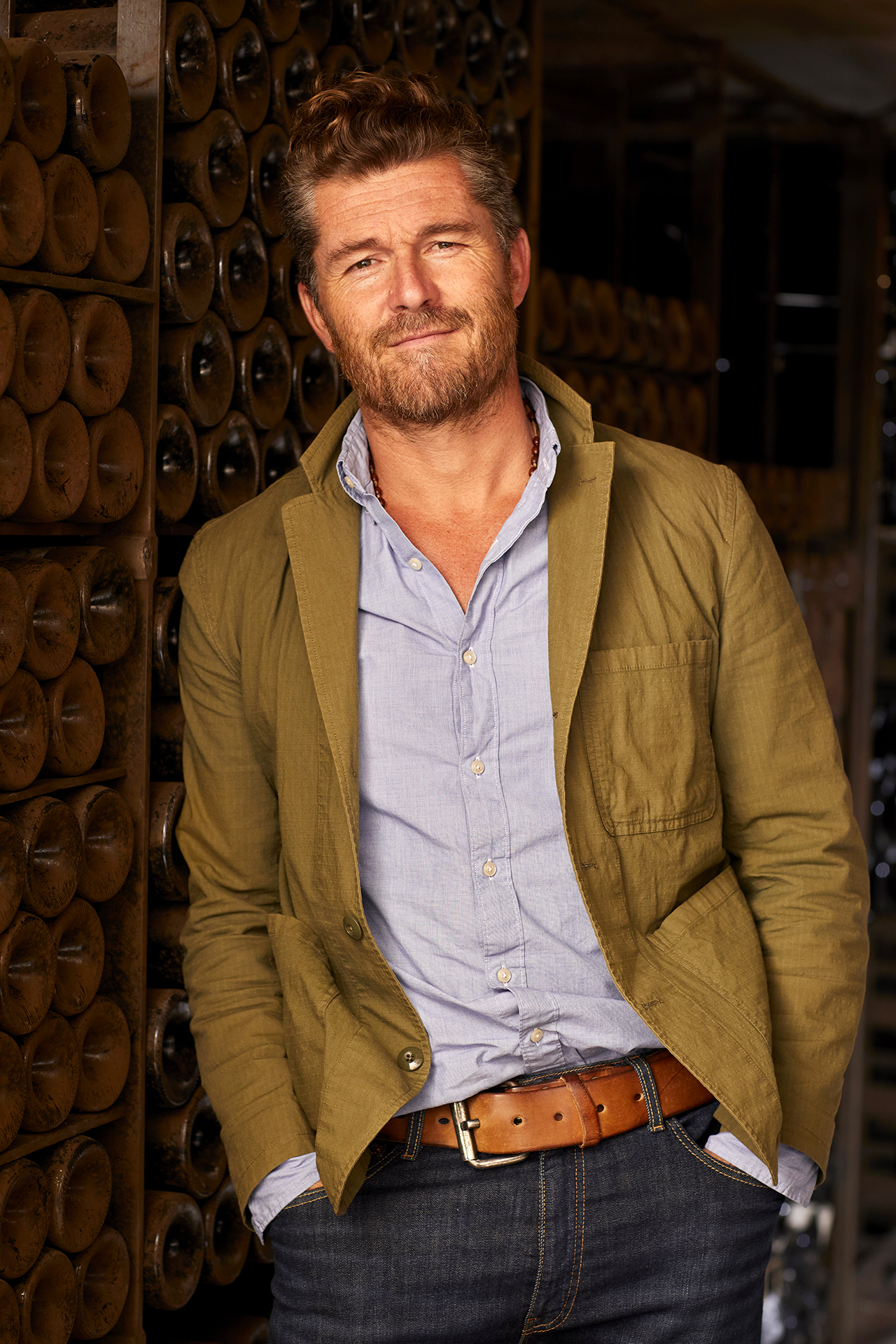

The iconic haute couture house has been producing wine for almost 30 years. At the head of Bordeaux’s Château Berliquet, Château Canon, Château Rauzan-Ségla, and Provence’s Domaine de l’Île, is Managing Director and globetrotter, Nicolas Audebert, who stands at #9 in the rankings.

Appointed head of Chanel’s vineyard properties in 2014, the talented Nicolas Audebert oversees three Bordeaux estates (Châteaux Canon and Berliquet in the Saint-Émilion appellation, Château Rauzan-Ségla in the Margaux appellation), and the Île de Porquerolles estate. With his casual appearance, tousled hair, and sun-kissed complexion, he exudes a rock-star charisma that has propelled him to magazine-cover stardom. The oenologist and agronomic engineer, who honed his skills at Krug before taking charge of winemaking at Cheval des Andes in Argentina, seems to possess the Midas touch, turning everything into gold. Whether it’s a classified Bordeaux Grand Cru or a Côtes de Provence rosé, this virtuoso of the vine knows how to craft excellent wine.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Nicolas Audebert: – I’m not even sure that I am a winemaking champion! I’ve been lucky enough to work for some very prestigious names that have helped me to get to where I am today. It’s the brands, the vineyards, the terroirs, and the people I’ve worked with that have brought me to where I am, a position where people might say that I’m some kind of champion, but really I’m not. There are scores of people who are far more competent than me. I take my hat off to all the small-scale winemakers who make fantastic wines for 15 euros a bottle, that nobody knows and who are the real champions, as their job is far more difficult. When you work for a big name, with substantial resources and great terroirs, it’s a whole lot easier.

Have you been training for long?

I don’t see it as training. I do it because it’s a real vocation: my love for grape growing and winemaking is behind everything I do. If we take the example of musicians or sports stars, there are those who achieve with hard graft, and then those who take real pleasure in it, who have a passion for it. Obviously, as winemakers, we’re constantly tasting things, and we probably taste other people’s wines more often than our own, to learn and understand. I’ve been making wine now for 25 years. I didn’t grow up in the wine world. I fell into it, I won’t say by accident, but because I loved nature and wanted to do something that involved being close to the land. Wine seemed an obvious choice: it allows you to transform an agricultural product into an experience that is emotional, sensory, cultural, historical. As winemakers, we have one foot firmly on the ground and the other up in the stars!

Who is your mentor?

We learn daily from everything – and everyone – around us. Whether it’s with a renowned South American oenologist, a Champagne cellar master, a wine connoisseur – I’m constantly discovering new things. I learn from talking to enthusiasts who’ve tasted everything under the sun, I learn from talking to winemakers who’ve been in the game decades. I was lucky enough to work with Rémi and Henri Krug for many years. I also worked with Maggie Henriquez, a rather exceptional woman, and with Philippe Coulon. I worked with Roberto de la Mota, the renowned oenologist from Argentina. I worked for 10 years with Pierre Lurton; he taught me a great deal. And I continue to learn every day with our estate workers.

Is wine a team sport?

Yes, it’s definitely a team sport. First of all, it’s a long-term process. Our team exists outside time – when we take a bottle of 1929 or 1947 Château Canon from the cellar, it’s the same team which made both wines. Great wines are not bound by the limits of time – they capture the essence of a particular place, a path, a destiny. We bear the weight of all that history on our shoulders; we need to write our own part in it.

There are many people in my team: first, the people who work every morning out in the vineyards. I’m not the one out there tending to the vines, pinching them back, tying them up, turning the barrels, racking the wine. After that, we have to blend and taste, with our consultant oenologists, Éric Boissenot and Thomas Duclos, and with our in-house winemakers. Beyond that, there’s also a little bit of Roberto de la Mota and Maggie Henriquez in my Saint-Émilion wines.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

Of those two elements, only one of them is indispensable: the terroir. If you don’t have an exceptional terroir or a distinctive winemaking signature, you won’t make good wine. That said, I don’t agree with the current line of thought saying that everything needs to happen by itself. Grapes that jump of their own accord into bottles and suddenly make great wines, without anyone doing anything, simply do not exist. You need someone to work on them, so it’s a union between the team that does that work and the terroir on which the grapes are grown – a bit like a horse and its jockey. It’s the horse that does the running, the winning, that has all the mental and physical qualities needed. But it needs a rider, to say “Go that way!” and to keep its pace steady at the beginning before sprinting to the finish line. That said, the ratio isn’t necessarily the same: it’s perhaps 80% horse and 20% jockey, whereas it’s probably 70% terroir and 30% winemaker.

If there’s nobody there to care for vines, and cut them back, they don’t make grapes, they just create tendrils and exhausted fruit. Without human hands giving them enough stress and direction, they won’t give anything. And without grapes, humans can’t make wine, so it really is the meeting of both, but a meeting where the winemaker’s style must be the expression of the terroir.

To what do you owe your success?

Above all, I owe it to my parents and to the upbringing they gave me. They taught me to be demanding of myself and of those around me, but they also imbued in me a respect for other people, a sense of patience, an ability to listen, boundless energy, and a desire to achieve, which means that I perhaps have certain qualities that make people want to go along with my projects and put their trust in me.

Is your family proud of you?

Yes, my family is proud of me. That said, the word “proud” sounds rather arrogant to me, a bit egocentric. I would like to think that the life that I am lucky enough to lead today – professional, social, and cultural – is something they look up to, rather than feeling pride for me. In my eyes, words like fulfilment, balance, and desire are far more important than pride.

Who is your most important sponsor?

If we’re talking in purely professional terms, it is Chanel. It’s a wonderful couture house which gives me the freedom to do what I do because it’s an organisation that understands you have to play a long game, and because it is run by people with a huge sense of creativity, who are striving for excellence. They are a truly extraordinary sponsor.

What is your favourite colour?

The colour of the soil, as it has so many different shades. There are ochre soils, red soils, brownish-black soils, sandy soils. It’s this mosaic of colours that allows us to make our great wines and bring complexity to them.

Your favourite grape variety?

I would have to say Malbec, as I hold a particular attachment both to the grape variety and to the wonderful country that is Argentina. It’s a grape variety with quite an extraordinary history, which ended up finding somewhere to call home on the other side of the world, in the most unlikely of places. It left Cahors and came to Bordeaux, where it was planted before disappearing again and going over to South America. It was planted first in Chile, then in Argentina; it crossed the Andes by horse, in the saddlebags of President Sarmiento and a French scientist called Pouget. And then, finally, it found a place in the foothills of the Andes, on the Argentine side, high up on the Altiplano plains, in a continental climate, where it felt at home and was happy.

Your favourite wine?

Amongst the wines that we have here in our cellars and that I have been lucky enough to taste, there are a few that are truly extraordinary, that mark you for life. There are certain vintages of Rauzan and Canon that I won’t ever forget, like 1964, 1955, and 1929, for example. They are all absolutely unbelievable wines. I have memories from all over the place, whether it’s in the Piedmont, in South America, in Burgundy, in Champagne. There are exceptional wines everywhere. However, if I had to keep just one bottle, the one that made the greatest impression on me, it would be Krug 1928, which has an incredible history. Bottles of this vintage had been seized by the Germans to be sold on the British market, but the British didn’t want them because they had been disgorged for a while, and Joseph Krug was able to salvage them. Bottles of Krug 1928 are almost 100 years old, and absolutely extraordinary.

Your favourite vintage?

I wouldn’t pick one that’s too old, or one that’s too young. I would have to say 2001 because, whether it was on the Right or the Left Bank, it made for an extraordinarily precise wine. It isn’t an iconic vintage by any means, but at the same time, it shouldn’t be overlooked. It’s not a small vintage, the wines it produced are very clear, very precise, they say what they have to say without shouting it from the rooftops, but rather with humility.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

My wines have a strong identity, they are the mirror of the land from which they were born. People often say that a dog is the reflection of its owner, but a wine must take after the place from which it comes. Today, you could make a wine in Margaux that was modern, sun-drenched, Mediterranean, extracted, powerful, with exotic accents – why not? But that is not what customers are looking for. Similarly, if you’re making, somewhere deep in South America, a wine without colour, that’s austere and cold – something is wrong. Wine reflects a culture, a path, and this path was set by the land, the climate, the people, and the wine needs to resemble this, it needs to be rooted in a very specific place. Take Canon for example, which has a very specific terroir, with clay-limestone soils, on the plateau of Saint-Émilion. This is a terroir that doesn’t lie, it’s a terroir where you couldn’t be doing anything else. When tasting a wine, people often make analogies to refer to its character. They often say: “This one is slightly withdrawn, it’s a little shy, you need to give it time. It needs to grow in confidence”. Or you could have a headstrong wine, that knows what it wants to say, and says it very bluntly and directly. I wouldn’t be able to make a wine if I didn’t have a clear idea of what kind of person it would be.

What are the best circumstances in which to taste your wine?

In good company. You should never drink alone, as wine is designed to be shared, to build bonds between people.

With whom?

Some people say that you should only open good bottles with people who understand wine, but I think that’s a real shame. In my eyes, you should open those bottles with anyone who wants to drink them, whether they understand or not. The pleasure, the sense of discovery, the satisfaction, and the emotion that great wines afford are within everyone’s grasp: those who know about them and those who don’t. Obviously, you shouldn’t open a great bottle with someone who won’t enjoy it, it wouldn’t make any sense. But if the desire to open it and share it is there, even the greatest bottle can be opened with someone who doesn’t know much about wines, because these moments are about conveying emotion, about passing on this immutable knowledge that exists outside of time.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wine?

I’m lucky enough – or unlucky enough – to be on a natural high all the time. I’d almost prefer for it not to be the case! However, I would never enhance my wine with chemical assistance. There’s this trend for souped-up wines but they bear no interest for me whatsoever. It’s far more interesting when things are full of surprises, when you gradually discover different aspects that bring complexity. This complexity is the opposite of in-your-face showiness. Chemically enhancing wines allows you to achieve a feat once but, behind that, there’s nothing, because it’s part of a system that is distorted from reality, showy, and short-lived. The point of wine is for it to be always true, and precise.

Who is your worst enemy?

I’m my own enemy – if I weren’t, life would be very dull! The hardest thing is to know yourself and to understand your own strengths and weaknesses. It’s always easy to talk about our strengths. Our weaknesses are much harder to work on. In the wine world, which is a world of pleasure, of shared experiences and emotions, I don’t really see any competition or enemies.

And your greatest achievement?

My only motivation is my family and our life together. I try to pass on to my children a bit of the upbringing that I received – with its values and traditions – but also an openness and willingness to discover the world. I still have so many things to do, places to go, wines to drink, countries to discover, people to meet: it’s this desire to be open to and interested in everything and everyone that I want to pass on to them.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

It is, above all, allowing ourselves to be innovative and not being scared of asking questions or implementing new things. In some places, the wine world is defined by a multitude of traditions; in others, it is all about constant innovation. It is quite rare for the two things to coincide. In the places where it’s very traditional, if you do things a bit differently, then it’s often very marginally so, just to be able to say that you do things differently. On the other hand, there are some vineyards, some regions, that aren’t bound by tradition, and are free to innovate. In a traditional vineyard, wanting to do things differently is ultra-modern and innovative in and of itself. When I arrived in Bordeaux, I had never worked in the region before. I had no qualms about implementing new ideas or developing things that didn’t follow the traditional Bordeaux way. You need a mix of both: one eye looking ahead and one eye looking back.

Can you give me an example?

Conducting several harvests within the same plot, for example, according to the exposure of the rows, and then vinifying the grapes separately according to this. Depending on the aspect of the row, some phases get more sunlight than others in the very warm years, with grapes that will be riper, spicier, darker, and more intense than others that will be fresher, more acidic, and have more tension. It’s hard to vinify them all together while staying precise, so in certain years we do several harvests within the same plot and vinify its grapes separately. Another example is the concept of having people taste wines straight from the barrel during en primeur and for the definitive blend, letting them can pick whatever barrel they want to taste from, which allows us to talk about the wine and be completely transparent about what we have in our cellars. There is a highly distinctive approach to tasting in Bordeaux.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

Pierre Lurton. One should always pay honour where honour is due!

Burgandy’s talented winemaker: “I juice myself up on Pinot Noir”.

For the 40th interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series, we return to the Morey-Saint-Denis to meet Jacques Devauges, who stands at #10 in the rankings. A staunch supporter of the Côte-de-Nuits, he is an advocate of excellence. From one estate to the next, he continues to pursue the same goal: expressing the nobility of the Morey-Saint-Denis terroir.

The former manager of Clos de Tart between 2015 and early 2019, Jacques Devauges joined Domaine des Lambrays that same year, moving from an estate owned by François Pinault to one owned by Bernard Arnault. It was “chance and a series of encounters”, he explains, that brought him to where he is today. Although nothing predestined him for the world of winemaking, he fell in love with it during a harvest season, with his baccalauréat in hand, at a small estate in Pommard. “After that, I met some intelligent people who put their trust in me”, he says with humility. Today, as head of Domaine des Lambrays, a leading Côte-de-Nuits estate, he intends to continue the work of his predecessors, while instilling a new energy and uniting a team around his most deeply held principles. Here, we talk to a modest man who listens attentively to his terroir.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

I distance myself a lot from these things. I’m incredibly lucky to be doing a job that I’m passionate about. When you get up in the morning and love what you do, everything is easy. So, I don’t see myself as a champion. The Arnault family trusts me and has handed me the opportunity to work with some extraordinary plots.

Have you been training for long?

I chose to work in the field. I have a degree in oenology, of course, but I started from the ground up.

Who is your mentor?

I didn’t really have one mentor in particular. I met Denis Mortet, a winemaker from Morey-Saint-Denis, who helped me a lot when I didn’t know anyone, then Christian Seely, the President of Axa Millésimes, who gave me the keys to the Domaine de l’Arlot, and finally Sylvain Pitiot, who I consider to be one of the greatest Burgundian winemakers, as much for his professionalism as for his warm personality.

Is wine a team sport?

Completely. You can’t do anything on your own. Before we talk about the wine, we talk about the vine. The sense of team spirit is strong because it’s rooted in time. It’s not just a horizontal team but also a vertical one, across the generations, and that’s what I find so powerful about our profession. It’s a real pleasure to come into a field and get your teams motivated by a project. You can’t have a vision on your own. You have to get everyone on board, not just the team, but your customers too.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

The terroir of course. It’s a bit of a cliché, but you need a great winemaker to make a great wine, it’s a symbiotic relationship. The climate is just as important as the soil and the work of the winemaker. All these elements have to be present for a wine to inspire emotion. That’s not to say that you should only drink grands crus costing thousands of euros. Emotion is the alchemy of a whole range of elements. That’s why wine is so fascinating.

To what do you owe your success?

I see myself as a student. Every year brings a new challenge, and you have to try new things, so I can’t explain my success, because I learn something new every year. This desire to adapt and observe is essential. You must remain humble and curious, and strive to produce pure, precise, clean wines that fully reflect the place from which they come.

Is your family proud of you?

My mother is, and always has been – that’s a mother’s role.

What is your favourite colour?

A very distinctive colour, that of very old Burgundies from the 1920s and 1930s, up to 1940. Pale in intensity, with a pinkish transparency and hints of faded pink, it could almost be a shade of tea. In a nutshell, somewhere between aged pink and tea. These are moments you remember for the rest of your life. Wine is also about working with the generations that came before us, and this colour is there to remind us of that. These are wines of impressive power.

Your favourite grape variety?

I’m a big fan of Pinot Noir, which is what moves me the most, but I also like Gamay grown on granite soils, and Syrah from the Northern Rhône.

Your favourite wine?

Clos des Lambrays has a fascinating terroir, something that everyone can see when they walk through the vines. There’s an extraordinary diversity that can be found in the wines, which have a very elegant mouthfeel. It’s because of this parallel with the landscape that I love it so much. Long before I arrived at the domaine in 2002, I tasted a Clos des Lambrays 1918, and it still impresses me now as it did then.

Your favourite vintage?

I like fragile, complicated vintages, which you can feel when you taste them. Decades later, they’re still standing. I’m reminded of 1918 or 1938, which are forgotten years, with a historic dimension.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

No idea, I don’t think it’s for me to say. Each one has its own identity, and I like to think that the identity of each wine is linked to the soil. We produce nine different wines, each with its own personality.

What are the best circumstances in which to taste your wine?

Whenever the mood strikes; it’s the opportunity that creates the greatest tasting moments. Sometimes a friend or family member drops by, and you’re drawn to one bottle rather than another. Those are the best moments. For our wines, you have to open them three hours in advance, without putting the cork back in.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wine?

I juice myself up on Pinot Noir. But at the estate, we have this ideal of purity, which means using as few inputs as possible.

Who is your most feared competitor?

The hazards of nature, which are extremely frustrating. No matter how hard we work, when Nature decides otherwise, she’s always right. Every vintage has its difficulties, to a greater or lesser extent, but we try to turn them into strengths. In 2021 for example, Nature was unkind, but a few years later, I’m delighted with this vintage, which I didn’t see coming, with the grace, elegance, and delicacy that we’ve come to expect from the climate. If you’re clever enough, you can make a friend out of it.

And your greatest achievement?

To see that my team at the estate is supporting me in this project. We went organic, then biodynamic, and it makes me proud to have a whole team who wasn’t in that frame of mind before, and who now couldn’t go back. And the customers, who are rediscovering Clos des Lambrays. These are the two driving forces behind our passion.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

At the estate, we renovated our facilities in 2022, which took us two years to complete. We developed a gravity system, which is very simple: in the centre of the building, we have two vats that go up and down, and the wine flows very naturally. We have developed unique wooden vats, ones that are not truncated. We’ve had cylindrical vats developed, which allow us to use a movable ceiling that forms a watertight seal, enabling us to keep our bunches whole before fermentation starts. This system allows us to avoid using acetate and to vinify in oak.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

I’d like to find someone who thinks differently from me, not about the fundamentals, but about how to get to them. Someone who takes this estate, these terroirs, and this domaine head on and finds their own way to express it.

Winemaker of the family-run estate: “We have never compromised”

Our next interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series takes us to Morey-Saint-Denis, in Burgundy, where we meet Christophe Perrot-Minot, #12, who continues to forge his own path and ruffle a few feathers along the way.

The former courtier, forever championing the expression of the terroir, and whose knowledge of viticultural regions informs the expertise of his Burgundian know-how, refuses to forsake perfection in the pursuit of profitability. The winemaker, aware of the allure of Burgundy’s Grand Crus, is driven, above all, by the desire to express the taste of his vineyard – a powerful voice, both refined and gracefully tannic, which impels you to listen. To hear it, nothing must be overlooked. Although the estate sources grapes from various plots across the Côte-de-Nuits, Christophe Perrot-Minot supervises every harvest, carried out by his own team, be it in Gevrey-Chambertin or Clos de Vougeot. Organically certified for the past few years, Domaine Perrot- Minot belongs to one of the most sought-after appellations, an appellation that is facing necessary changes to preserve its nature. This challenge – to reveal what the land does not give you outright – is one the winemaker takes up with gusto.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Christophe Perrot-Minot – I really don’t consider myself to be a winemaking champion, it’s not something I’ve ever thought about.

Have you been training for long?

I’ve been training for over 30 years. I arrived at the estate in 1933 and before that, I had played at being a wine broker for seven years. This gave me a great overview of what everyone was doing: I could walk into a cellar one morning and meet someone who was struggling to solve a certain problem; a few hours later I would walk into a second cellar where a different person had faced the same issue and solved it years prior. Just like that, I would bring the solution back to that first person. This helped me take a step back and gain perspective on this profession. That experience was the intellectual key, the key to realising what I wanted to be doing, the key to achieving the result I had in mind, to obtain the style of wines that I wanted.

Who is your mentor?

My only mentors have been observation and reflection, because at the end of the day, I have never collaborated or vinified with my father. When I joined the estate in 1993, he handed the reigns over to me. For everything related to vinification, I had a pretty clear vision of what had to be done and avoided, a vision that was in opposition to the previous generation’s, who cared more about production. This had a lot to do with the education of the time. When I first arrived, I had ideas that went against those of my father in terms of lower yields, of sorting – all these things were very hard to accept for that generation. They had been told, in the 1980s, that you needed to plant productive clones. There was a time when Burgundy was more focussed on quantity than quality. We had to fight to switch gears and convince people, for example, to throw out grapes. Things didn’t change in a year! As for the sorting, we implemented it as soon as I started, but accepting this practice took much longer.

Is wine a team sport?

Wine is a team sport. Everyone needs to understand what direction we’re going in and accept it. You also need to surround yourself with competent people. You can’t make wine, let alone good wine, without a team. A winemaker can’t do everything themselves. You mustn’t forget that it takes many hands to craft a wine. All those hands, put together, give the grapes their potential. And this before even mentioning their provenance, the terroir… I also know that my opinion needs to be contradictory, and I have a right-hand man at the estate with whom I talk about different options regarding the bottling, harvest dates, and many other parameters. I think you move forward more efficiently when you can eliminate any doubt or hesitation. For me, the key to success is having a competent team you can exchange ideas with in order to move forward. I often like to say that they would be nothing without me, and I, nothing without them.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the team?

It’s always easier to make a great wine with a good terroir. But in a team, everyone is moving in the same direction, and you can express the terroir with even greater quality.

To whom do you owe your success?

I think the estate’s success is linked to the people that work there, and to our relentless pursuit of quality. That is, we prioritise the intrinsic quality of the grapes during vinification. We don’t think about the bottom line when we’re sorting them, or that we’re getting rid of “Grand Cru” grapes. We don’t calculate how much we’re losing when we discard some of them. No. We have a clear vision that is entirely based on the grapes’ intrinsic quality, without worrying about the appellation. I think for us, there is a lot of discipline and very little compromise – perhaps no comprise at all – on how the grapes that enter our vats need to be.

Who has been your biggest sponsor throughout your career?

Our best sponsor has been consistency. By which, I mean that we have never compromised. Whatever the vintage, we have always managed to keep the best grapes. “Whatever the cost”, as our president would say (a political doctrine coined by French president Emmanuel Macron during the Covid-19 outbreak, ed.). Whether we’re sorting Burgundy, Morey, or Chambertin plots, the process will always be the same. Why? Because I think all wines reflect an estate, its ambitions, its absolute character, and that of the people who work there. So, this refusal to compromise is a form of self-respect, and of respect for our clients. Moreover, everyone knows that Burgundy wines are expensive, but you mustn’t forget that there are people willing to pay €30 or €40 for a bottle of Burgundy – and I’m talking about the Burgundy appellation – which is a fortune. This might be the most they spend on a bottle in a year. And that’s why the estate’s most affordable bottle must be faultless. This is what I think.

Your favourite colour?

Red. In all its different shades. You can find a lot of different personalities in reds.

Your favourite cuvée?

The Mazoyères-Chambertin. Because it’s an appellation that I’m in the process of reviving. Everyone knows that when you’re making Mazoyères-Chambertin, you can call it Charmes-Chambertin. For marketing reasons, or for ease, it’s sold under the name Charmes-Chambertin. When in reality it has a completely distinct personality from Charmes-Chambertin, and it deserves to exist independently.

Your three favourite vintages?

The 1993, because it was my first. The 2003, because it was my first time vinifying an extremely hot harvest. After that, I would say the one that followed.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

It would be the people that made it.

In that case, would it be you?

Even though it’s the product of teamwork, the style is personal. My team is so committed, that they will work to achieve the style that I want to see, that I’m looking for. My desired style is balanced, elegant, and refined wines. With tannins that are integrated, silky. Wines that, I would say, can be good regardless of time. I always think of Henri Jayer (a French producer credited with introducing important innovations to Burgundian winemaking, ed.), who used to tell me: “Christophe, a good young wine makes a good aged wine” and “a good wine needs to be good at all times”. It was so simple yet so true.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing your estate?

What really led to a change in quality, beyond the work and everything we have done these past 10 years, was our organic conversion, despite being long overdue. With this organic conversion, we noticed how the wines became more transparent and luminous. The juice became much more precise. And this increased the quality massively.

For what price would you be prepared to sell your estate?

You can’t sell something you’re only renting, so it is not for sale.

France’s 13th best winemaker: “I love drinking fine wines with people who know nothing about them”.

The mere mention of the name of this Grand Cru Classé is enough to send wine-lovers into a frenzy, and even those who have never had the chance to taste it agree that this is a Château destined to go down in history.

For the 38th interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series, we return to the border between Pomerol and Saint-Émilion, and Château Cheval Blanc, which is owned by the LVMH group and the Frère family. In July 2023, Pierre Lurton was appointed President of the Management Board, while Pierre-Olivier Clouet was promoted to Managing Director – arguably one of the most globally envied positions in the Bordelais appellations. Clouet, who describes himself as “incorrigibly hyperactive”, joined the estate as an apprentice but rose through the ranks with the elegance of a cat, gradually gaining the trust of Pierre, his mentor and great friend, who conferred on him the role of technical director at the age of 28. As well as his charm and extraordinary capacity for work, the fact that he did not come from a wine background was a considerable advantage for the young Norman, who very early on dared to “say out loud what others were thinking”. He is a free and rebellious spirit wrapped up in the demeanour of a gentleman farmer and bears a humility that allows him to assert his ideas with great ease.

“When I think about it, it was surreal”, he recalls with a burst of laughter. “At first, the suit seemed much too big for me”. The future proved him wrong, and it was alongside a close-knit team that he succeeded, one by one, in meeting the challenges posed to an estate that had to demonstrate its modernity without ever denying its roots. Creating a white wine from scratch, opting for agroforestry, finding plots of land at the foot of the Andes – all of these challenges have been overcome thanks to “the stability that Pierre has been able to give me for many years, which has allowed me to see each of our developments through in the long-term”.

Le Figaro Vin – How does it feel to be crowned a wine-making champion?

As always, I wonder why I was chosen! It’s something I’m very proud of, and I’m delighted that people come looking for me. 15 years ago, I was a nobody, and I never had a career plan. I feel both very grateful and infinitely small.

Have you been training for long?

Not really, no. Some winemakers made my eyes light up when I was a student, I wanted to “be just like them”, as children say. It’s an environment that allows you to come into contact with so many different disciplines – there’s the agricultural side, the technological side, the emotional side – and you meet people you’d never think you’d meet.

Who is your mentor?

First and foremost, it would have to be Pierre, who gave me a chance at a time when nobody could see what I could bring to the table. He’s always been kind, letting me off the hook as I’ve developed and gained confidence in myself. He supported me, and even though we have different personalities, I owe it all to him.

Is wine a team sport?

Yes, without question. Especially in our maisons, because on a small estate, there is a stronger representation of the winemaker. Here, we have a lot of input from everyone, from all those who have inspired us from near and far, and in particular from the people who have accompanied us through all the transformations we have undertaken. Cheval Blanc is too much for just one person.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

What makes a great wine is the terroir, but what ensures that it doesn’t fail is the winemaker. In our vision of a cru, rather than a brand, our task is to convey the taste of the region. Vintage is also of absolute importance.

To what do you owe your success?

Sincerity. I’m not a schemer, I have an ability to get people on board, to unite teams. And I’m hyperactive, so that obviously plays a part too.

Is your family proud of you?

Yes, and I think it’s wonderful that my family isn’t from the wine scene. It takes me out of my microcosm and brings me down to earth. You have to go out into the real world, where you can enjoy simple wines. My parents still marvel at the bottles I open for them from time to time, and that’s fantastic. When I think about it, I love drinking great wines with people who know nothing about them.

Your favourite colour?

Red, even though white wines, which I’m drinking more and more, have a great deal of precision. I think you can read more about the terroir in red wines, particularly through the tannins, which reflect the way in which the vines have been able to draw on what the land has provided.

Your favourite wine variety?

Cabernet Franc, because it is the father of all Bordeaux grape varieties. It has spawned much more popular offspring that itself, notably Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, but it has the advantage of being versatile and offering enormous diversity.

Your favourite wine?

I’m a big fan of Mas Jullien (in the Terrasses du Larzac appellation, ed.), which is a wine of tremendous precision, and in particular the Autour de Jonquières cuvée.

Your favourite vintage?

2018, which is a truly spectacular Cheval Blanc.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

Chopin, for its universality, emotion, timelessness and classicism. His first concert took place in Paris in 1832, the year the estate was founded in its current guise.

What’s the best way to enjoy it?

With nice people. It’s such a complex wine. A great wine shouldn’t be tasted for what it is, but because it can provoke great conversations.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wine?

No, never. That’s one of the most important things: we don’t allow ourselves to modify our grapes. Expressing a terroir does not mean upsetting its natural balance. You learn as you get older that you must do as little as possible.

Who is your strongest competition?

The weather, and that’s just for starters. It’s an increasingly tough opponent, and if we win today, it’s doubtful that we’ll win again tomorrow.

Which competition do you dread the most?

Bottling. It’s the last moment we actually see our wines. From that point on, they no longer belong to us. After that, I have no more expertise than a collector. I know how to assess our wines as they are made.

What is your greatest trophy?

Getting the message across that there was a whole other debate going on in the wine world than just about the differences between organic and biodynamic winegrowing. You must understand the life of your soil, the need to get rid of monoculture and bring back diversity. This is the future of winegrowing, but also of humanity. I’m proud to have played my part, rising above the petty arguments that drag the debate down. The battle isn’t over yet, but we’ve made a step in the right direction.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

I don’t know at this stage, perhaps a future former trainee. I’d like it to be a woman because that would be a first. Although we’re not a family estate, our owners have a very family-orientated vision of the vineyard, and the notion of succession through the generations is essential.

Father and son winemakers of their family estate in Alsace: “We like the idea that wine finds a voice of its own, independent of the winemaker”.

For the 37th interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series, we return to the Route des Grands Crus d’Alsace, to meet Mathieu Deiss who, together with his father, stands at #14 in the rankings. Since its foundation in 1947, in Bergheim near Ribeauvillé, Domaine Marcel Deiss has been cultivating high standards, respect for tradition, and the capacity to evolve. This is a family history where the exchange between father and son transcends simple sharing of knowledge.

Mathieu Deiss needs no invitation to pay tribute to his father, Jean-Michel, who continues to help him run the estate. Alongside his commitments at Domaine Marcel Deiss, Mathieu also devotes himself to a more personal project at Vignoble du Rêveur (The Dreamer’s Vineyard), together with his partner, Emmanuelle Milan (daughter of Henri Milan of Domaine Milan, ed.). And you truly have to be a dreamer to imagine that the coming together of heaven and earth has given birth to a divine nectar, historically dedicated to the gods, today aimed at humans instead. However, for this “manual worker who also likes to handle ideas”, abstraction has its limits, as nature is always quick to remind us.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Mathieu Deiss: More than any personal gratification, what really matters for me is the appreciation of the work that goes into every bottle, not least the work of my father and my partner. I see this as recognition for the estate rather than for me personally. I find it touching, and it inevitably makes me think of the 25 people who work alongside us.

Have you been training for long?

I grew up surrounded by tractors and wine presses, I have been immersed in it all since I was a baby, just like Obélix. Without being remotely aware of it, I have been trained by my circumstances, and I owe that to my father who gave me all the freedom I needed. I am a manual worker who also likes to handle ideas. When I started here in 2008, after completing a degree in physical chemistry, my father was beside me in the cellar to help with my first vinification. It has been a genuinely seamless transition. I never wanted to act out the father-son generational schism. Great wines are a complex affair, to do with conserving something and with breaking new ground. I like to combine the best of both worlds. There will always be people who find me either insufficiently “natural” or insufficiently conventional. I like the idea that wine finds a voice of its own, independent of the winemaker. There are aspects of vintages and of the character of every terroir that require us, the winemakers, to stand aside from the limelight. Especially in Alsace!

Who is your mentor?

My father has played a central part in my career. He has frequently proved to be right while ahead of his time. Stéphane de Renoncourt has also been a big inspiration. He has a real sensitivity for wines. Wine is not just about slavishly following traditional methods; it is also an adventure, and you have to change what isn’t working. You have to stay agile, which is not always easy in the world of wine. We might even go as far as to question the wine appellation system and ask whether it is sufficiently adaptable. I can understand that natural wine is outside the mainstream, and we have to accept that. However, some grape varieties and some methods have now passed their use-by date.

Is wine a team sport?

Yes, you have to be able to play as a team and get people on board with your programme, but it’s also very solitary at times, because you have to take risks, stand on your own two feet, develop your own style, and make your own decisions. You can’t ask the team to take all that on. You can’t paint a picture with ten of you at the easel. The trickiest time is when it comes to bottling. That is when all the doubts set in.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

You can put your best efforts into a very simple terroir and that regularly produces great wines. You cannot have one without the other. The terroir is paramount, if for no other reason than it provides an essential continuity. When it comes to the winemakers, there are more disruptions, because of family transitions in particular. We want to give our terroir its own voice.

To what do you owe your success?

I was lucky to be in the right place at the right time, as Brassens put it. However, I think I owe my success to tenacity, and that goes for my father too.

Is your family proud of you?

I think so. We shouldn’t do what we do with the aim of impressing others. But when my partner, Emmanuelle Milan, and I had forged our own path with Vignoble du Rêveur, I’m pretty sure that finally convinced my father that I was capable of taking charge here.

What is your favourite colour?

I’m far too curious and fond of variety to pick out one colour. My wines reflect that. I mix white with orange, find something of interest in everything, and I operate more and more by instinct. I think that red wines have a great future in Alsace, where the changing climate will suit the expression of Pinot Noir. I very rarely open bottles of my own wine, and I always taste completely blind to avoid being influenced by labels.

Your favourite grape variety?

Many come through alright, depending on the year, while some have, quite wrongly, acquired a bad reputation in the past. What bothers me is this obsession with focusing on a grape variety. What really engages me is rummaging around amongst the old Alsatian grape varieties which have disappeared for the wrong reasons. As soon as we started to use fertilisers some grape varieties produced two times too much and we tore up the vines, just like we did with those that didn’t tolerate grafting. Societal and climate change has turned all that upside down.

Your favourite vintage?

The recent vintages have been hot vintages, but 2019, for example, doesn’t taste of heat and is a really lovely vintage. The vintages which have provided exceptional ripeness seem heavier, and so atypical for Alsace, but they have very fine ageing potential.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

My personality is quite fastidious and particular. I think that this demanding quality can be found in my wine. I am a great lover of photography, and Henri Cartier-Bresson in particular. He captured the moment but was always reflective, his work combines a sense of movement and construction, and that’s what I want to reproduce in my wines.

What are the best circumstances in which to taste your wine?

I think our wines are wines that need to be shared. I never open a bottle on my own; it’s a shame for the bottle and a pointless exercise. Around a table, in company, remains the ideal, but for me, above all, these are moments for reflection. I want people to ask themselves questions and for that to generate discussion. I like wines to tell a story and for people to be stirred up.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wine?

No, the question has never come up. That’s all to do with economic considerations and that’s not why we make wine. 40 years ago, when my father went out on a limb, no one could understand it. He was also taking an economic risk but never looked at it in those terms.

Who is your most feared competitor?

Myself. The winemaker’s number one priority is to try to avoid making too many silly mistakes. Sometimes you have to be wary of yourself and your fears, which are seldom good advisers.

And the competition that you dread the most?

Bottling the wine. That’s the stage which makes me most anxious.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

It’s pretty much all been done before. Our predecessors have already done so much. Where I have done things differently I have been inspired by what people did in the past: putting grapes at the bottom of the barrels, for example, or reintroducing maceration, which is a method I would like to bring back into fashion. It allows you to play with the structuring of the wines, to improve their ageing potential. It’s not necessarily that tangible, but it gives the wines a spine.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

Perhaps one day my children, but it has to be their choice. We have four-year-old twins who wake up to help us at harvest time, so that we finish more quickly! Life runs its course. I have come across many sad people who haven’t done what they wanted to do in life. I hope, above all, that won’t be the case for my children.

Managing Director and winemaker of Château La Conseillante in Pomerol: “A great wine can’t exist without a great terroir.”

The 36th interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series takes us to Pomerol, where Marielle Cazaux, #15, has been at the helm of Château La Conseillante since 2015. Mixing the farmer’s wisdom of her upbringing with cutting-edge technical knowledge, Cazaux has brought a breath of fresh air to the prestigious Pomerol domaine. Under her reign, La Conseillante’s recent vintages have grown in quality and precision, becoming ever more refined while remaining faithful to their identity.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Marielle Cazaux: I wasn’t expecting to be in the rankings whatsoever! I was totally blown away. I heard the news when I was mid-harvest amongst the vines and all I could say was “Oh my God!”. However, I don’t see my work as something done solo, it’s very much a group endeavour with my team. If La Conseillante is where it is today, it’s thanks, in large part, to the team I have around me of people who are passionate about their work, who believe in my ideas and bring their own to the table.

Have you been training for a long time?

I have been in training since my very first internships as an agricultural engineering student, so since 2001. The first internship I carried out where I was really immersed in the world of wine was at Ridge Vineyards in Sonoma County. Afterwards, I went on to do an internship at Suduiraut in the Sauternes. When I started working in 2004, just after I graduated, I was taken on as Technical Director at Château Lezongars, in the Côtes de Bordeaux appellation. The property was 38 hectares, so actually quite big, but there were only four of us working there. I looked after the winery on my own, and the tractors too – if any of my workers were ill or on holiday, I had to look after the vines, treat any diseases, do the pruning, etc. It was a huge learning curve! I can still see myself in a tractor up at the top of a steep slope, between two rows of vines, saying to myself: “Come on, girl, you can do it!” It’s by training that you make your way up from the lowest divisions to the Premier League. With Château de Malleprat, I started playing in the professional divisions, and then Château Petit-Village (also in Pomerol, ed.) was my move into the Premier League. Now, with La Conseillante, I’m in the Champions’ League!

Who is your mentor?

My best mentor is my partner. It’s thanks to him that I ended up at La Conseillante as, when I was initially headhunted, I didn’t dare go to the interview as it was for Managing Director and not Technical Director. I’m a winemaker – I couldn’t see myself doing the sales and marketing part of the job. My husband, who’s a former rugby player, said to me, “In rugby, if you get up to the first division and it doesn’t work out, you can always go back down to the second division.”

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

In my view, a great wine can’t exist without a great terroir, so the terroir is more important. That said, you can’t make a great wine without a great team. In order for all the stars to be aligned, you need a great terroir, a good captain, who surrounds themselves with an excellent team, and supportive owners – for us, it’s the Nicolas family (owners of La Conseillante, ed.) – who believe in the team’s ambitions and give them the means to do things well.

To whom do you owe your success?

I think I owe my success to the wonderful childhood I had in the Landes. If, today, I’m blessed with a good nose and a taste for the finer things in life, it’s because I had a mother who was a fabulous cook and a father with an exceptional nose, who gave me a taste for wine. They both taught me to pay attention to everything I smelt and ate. You can’t be a great winemaker if you don’t pay attention to smells and to tastes, and if you don’t have a clear idea of what you like when you make wine. You need to have been lucky enough to have tasted lots of wines and to know what you like and what you don’t like.

Are your parents proud of you?

Yes, they are proud. However, I think my parents would be happy regardless of what I do, as long as I have a roof over my head and I’m content! They’re very down-to-earth, pragmatic people.

Who is your best sponsor?

Let me show you the label on my jacket. Can you see the little logo? I have a boss who adores clothes and who makes us all sorts of sweatshirts, polos, jackets, etc., all of which are lovely. My best sponsor is definitely my boss!

What is your favourite colour?

You can see my favourite colour right behind me – the blue of a cloudless sky, which gives you a feeling both of the vastness of the world and of deep contentment.

Your favourite grape variety?

It would be impossible for me to choose anything other than Merlot, even if I adore the majestic Syrahs of the Côte-Rôtie. A great Merlot produced on our Pomerol terroirs is just magic. It’s good young, then it’s good at 10 years old, at 15 years old, because it starts to take on truffle aromas. In the right environment, it is a magical grape variety, and its aromatic expressions are so wonderfully diverse.

Your favourite vintage?

Today, I’m going to choose a vintage that I didn’t make myself. I’ve only been at the estate for eight years and you have to wait at least 10 to 12 years for a Conseillante to be truly great. My favourite vintage is 2005. It’s a very emotive wine, with its many flavours, its complexity, its smoothness, its length, its finesse. It is, quite simply, a magnificent wine.

If your wine was a person, who would it look like?

I would say Miles Davis. In his music, there’s always the most wonderful smoothness and precision. His pieces are also utterly enchanting, exhilarating, and very long. I hope that the wines that we produce at La Conseillante today have that same balance, length, smoothness, and perfection, because it is perfection that we are constantly seeking.

What are the best circumstances in which to taste your wines?

If you only have one bottle – a 10- or 12-year-old Conseillante, for example – it’s best to taste it with just one other person so that you can both really get the most out of it. My husband and I have already tried tasting a bottle with six of us there. It is somewhat frustrating, as you can’t make out all the different aromas in all their depth with just one glass. Many people ask me for food pairings with La Conseillante and I would say that you need something simple, so that the dish doesn’t hide the wine’s aromas. You can start the bottle before the meal as an apéritif, with a little bit of pata negra ham, and then take the bottle with you to the table to accompany a very simple dish.

With whom?

With someone you love, whether it’s your partner, your parents, or your best friend. The best bottles are always those that are shared with the people that you love.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wines?

No… in fact, yes, I have a magic potion, just like Asterix, that I drink every morning during the harvest to stay on top form. I’ll give you the recipe – it’s fantastic! You need to put some water, fresh grated ginger, grated turmeric, the juice of half a lemon and a bit of pepper into a bottle and keep it in the fridge to infuse overnight; in the morning, you filter it. For wine, however, there’s no need to enhance it chemically. Quite the opposite, in fact, the movement over the last few years has been towards “less is more”, so no chemical inputs, less use of wood. We use indigenous lactic bacteria at La Conseillante: I take my bacteria from a particular parcel and I use them to make a fermentation starter for the following year. We don’t use any sulphur in our winemaking process, or only the barest minimum.

Who is your most feared opponent?

I have two opponents. Well, journalists aren’t really opponents but, for me, they cause a lot of anxiety with the scores that they publish for each vintage. It is a real source of stress for me, rather like for a designer who’s presenting his new collection on the runway. Something that is even more unpredictable and over a much longer period of time is the weather, which is my number one worry. From 1st April to 15th October, I have to live with the weather and its constraints. It’s not an opponent as such, as I can’t fight against it, but it is a form of adversity.

What are you proudest of?

First of all, I’m proud of having built the team that I have now at La Conseillante. Between the moment I arrived and today, it has changed considerably: some members have retired; others have changed paths. Today, however, I have managed to bring together an incredibly close-knit group of people that I like to call my “dream team”. Everyone is willing to work and not a single person complains. When we get a good rating for a wine, everyone rejoices. We eat meals together; we are a real team with a solid core, and I am very proud of that. It’s also thanks to the Nicolas family that I have been able to build this team up. Working for them is another great source of pride.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the winery?

If I give it to you, I’ll be betraying my deepest secrets… No, I’m just joking. I’ll give you something that I started using this year, which is really at the forefront of innovation, something quite mind-blowing, which comes from the world of neuroscience. We use electrodes, planted into the vine, to measure electric flows. We have a form of artificial intelligence that transforms the data into information that tells us if the plant is being attacked by mildew or if it is in hydric stress; it can even tell us if the grapes are mature. We tested the tool to see if, when the plant was telling us that it was in hydric stress, the results correlated with those of our traditional tools. We were astonished to find that it was completely accurate. It can also measure the berry sugar accumulation just by using these electric flows. Once again, the results recorded were completely accurate compared to the other tests that we carried out. All this means that the plant is using its own form of communication. Here at La Conseillante, we always thought that was the case! We speak to our vines, saying “good morning” to them at the start of the day and “goodbye” at night. In any case, this is the most innovative tactic that I have been able to test this year. In the winery, on the other hand, I think you have to stay very basic and return to traditional methods.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

I’m thinking of people who head up less prestigious domaines, who would so deserve this honour. I have lots of friends who make exceptional wines in the Côtes de Bordeaux, Côtes de Blaye, and Médoc appellations, who don’t get any media attention. So, go out there, go and do a ranking of France’s top 50 winemakers excluding Grands Crus and big domaines! Thinking back, when I was heading up lesser-known châteaux, like Lezongars and Malleprat, we made superb wines. I put in just as much energy and passion to my work then as I do now at La Conseillante. I’m thinking of all those winemakers who do a remarkable job, including my friends the Lavauds at Domaine Les Carmels or the Julliots at Domaines SKJ in Listrac.

The 35th interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series finds us once more in Champagne to meet Vincent Chaperon, #16 of France’s 50 best winemakers and cellar master of the emblematic champagne house: “I have quite an extreme nature”.

With his slender and athletic physique, preppy haircut, sharp gaze framed by thick-rimmed eyeglasses, and perfect diction, Vincent Chaperon is the kind of person one could easily find annoying, as he seems to have been unfairly graced with every enviable quality. But digging deeper, one might also sense a darker part, an urgency, and an eagerness to do well that is at odds with the hazardous conditions of a career that is at the mercy of its environment. Yet it is this tension, this fear of failure, that has crowned the young cellar master with success after success, where others might have settled for safety. “My time at Dom Pérignon has been something of a Bildungsroman: I was plucked straight out of school by my predecessor, Philippe Coulon (who passed in June 2023, ed.), and then raised in the maison” he recalls. “Despite my Bordeaux upbringing, to which I remain very attached, my adult life took shape in Champagne.”

Following a brief trip abroad, he was named oenologist in 2000, forming a virtually symbiotic duo with his predecessor Richard Geoffroy. “I arrived here with many expectations and ambitions, I wanted to prove something, and I had the chance to be inspired by people whom I loved very much, such as Richard, who helped me make the right decisions at times when I was growing impatient.”

This restraint bore its fruits: in 2017, the maison announced that he would be appointed cellar master the following year. “That day, I walked down the same hallways I always did, but everything had a different dimension, I looked back at the path that brought me here. It was an incredibly emotional moment.”

For the past five years, Vincent Chaperon has followed his ambition to fully embrace his role, without ever sacrificing its creative and sensitive dimensions on the altar of the operational. Eternally dissatisfied, he nevertheless describes himself as “profoundly happy”.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Vincent Chaperon: “I’m overwhelmingly happy and grateful to be where I am today. There is something exciting about this acknowledgement, that I really enjoy, because I am a fierce competitor. My friends call me “champion” because I’m always up for a challenge!

Have you been training for long?

Yes, for a very long time, at times excessively. I’ve always been conscientious and engaged. It’s a gauge for me: in moments of doubt, when my motivation is low, when I question myself. I have a real thirst for life, for this career, for people.

Who is your mentor?

Three people have guided my career. Firstly, my paternal grandfather, who was an admiral in the marine, on the Libourne side of my family. He passed on to me his passion for wine, indirectly and subtly. Later, Philippe Coulon and Richard Geoffroy, at Dom Pérignon. I was also lucky to meet Jeff Koons, who, in just a few hours, made me realise things about my career that resonated with me, particularly its eminently artistic dimension. More recently, I crossed paths with the chef Massimiliano Alajmo: we understood each other right from the start. These are people who open doors.

Is wine a team sport?

Totally. With a maison the size of Dom Pérignon, you need to know how to share, which is both a blessing and a curse. Having a common vision implies having a close-knit team for the long run, because you need to understand each other beyond words, through emotions, through memories.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

Both. I consider a “fine wine” to be first and foremost the story of an encounter between Nature and Man – which I don’t see as being in opposition, as long as humans work in harmony with their surroundings and strive to enhance Nature’s fruits. One must choose a place and attempt to give a part of oneself in return.

To what do you owe your success?

To this thirst I mentioned earlier. I have quite an extreme nature, unpredictable, I like to see things through and to do so in a radical fashion. I lost my brother early in life, and my thirst for life is unquenchable. Various encounters I made were also decisive, and one must put their faith in providence. I truly believe things happen for a reason. The people you meet have an impact on your path in life.

Is your family proud of you?

They are proud of who I am. I have often tried to compartmentalise, to find the right balance, but I’m realising that if I want to grow as a person, whether on a personal or a professional level, I need to be both mind and body. This is something that gives me a lot of thought. We are living in a very rational world, which thinks intelligently, through concepts, but we sometimes forget we are also bodies. One must have a holistic approach to better understand one’s heritage.

Your favourite colour?

Navy blue. Beyond being my favourite colour to wear, it says something about me: both my grandfathers were sailors, one admiral and the other a naval commissioner, and I think I am a sailor myself. In a way, this is my heritage.

Your favourite wine variety?

Pinot Noir, which I discovered through Dom Pérignon. It fascinates me. I love its tension, its versatility, its elusiveness, its fragility, it says a lot about us. And I say this as a Merlot man, which is not a contradiction!

Your favourite vintage?

2022 – I’m very attached to it, and had a very strong emotional connection with this vintage. Since 2018, I have always gone further, to affirm myself, to chart my own course, and this is what is conveyed in this vintage.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

It would be the person who is enjoying it. Wine is the mirror of people, and what I am seeking is for people to have a connection with our wines.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wine?

No. When I arrived, at 23 years old, it was like arriving at the town hall and seeing the motto “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité” (“Liberty, Equality, Fraternity”, the French motto, ed.). At Dom Pérignon, simple and natural winemaking was the house philosophy. It was quite visionary. There has always been a willingness to be transparent, to not overuse oak. There had been some in the 1960s, but when we started to work with stainless steel, everything changed. We have strived to build balance and complexity through the fruit, the blend, and time – these are the three essential components.

Who is your strongest competition?

Me. This taming of the self, this quest for knowledge, what our calling is, and wondering where we bring the most to the world.

Which competition do you dread the most?

Marathons. I have run three to this day, and notice that, although I can go the distance, I am still an impulsive person. I need to learn to endure waiting over time. My objective for next year is the New York marathon, and I am going to train to experience it fully.

What is your greatest trophy?

My family, and my role as cellar master for Dom Pérignon, which is a reward rather than a trophy, because it is not something I display.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

I have made many changes thanks to my research, such as making creative decisions early in the process. This means having very strong cultural and emotional biases for what is going to go into each vintage. I want to blend technique and emotions to give things direction from the start. This requires making the body and intuition priorities, through observation, tasting, etc.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

We are not a family-run maison, and yet, we think of things over the long term, with long-lasting mentorships, in ways that are similar to family bonds. There may not be a set candidate today, but there are many people that I am watching over and accompanying along their career path. I truly believe in working in pairs, in complementary duos. Ideally, my successor would be a disciple in the Eastern sense of the word, someone who is here for the long run, who can prove themselves. At Dom Pérignon, one must approach this holistically: right brain, left brain, concrete and conceptual, with true emotional intelligence. In the end, I would want it to be a good person.

Co-owner and winemaker of his family estate in Arbois: “I got ahead by turning to the past”

The 34th interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series finds us in the heart of the Jura, where Stéphane Tissot, #17, runs his family’s 50-hectare biodynamic estate. The 53-year-old now embodies one of the region’s most emblematic vineyards, inspiring and training a whole generation of future winemakers.

Over the years, a number of key encounters have led Stéphane Tissot to adopt a radically different approach to that of his father (Hervé, ed.), “who did a good job, but in a very classical style”. Having grown up amongst the family vines, 1990 was his first vintage. As with many young winemakers, he first made his mark in the estate’s cellars, where he put a stop to the practice of stirring the lees in the Chardonnays, before reducing chemical intervention on the vines as much as possible. While working in an Australian vineyard during the off-season, he found himself opening the same packet of yeast as the ones being used in France. “I realised there was a problem, and that’s what encouraged me to move towards a healthier way of growing grapes and making wine.” His shift towards organic methods allowed him to unlearn everything that his years of study had tried to instil in him: “At the time, we were going completely against the grain of what was being done in the Jura,” he acknowledges. “In our region, you can make any kind of wine: light reds, concentrated reds, dry whites, oxidative whites, crémants, the list goes on!” Despite having now made more than forty different wines and almost ten ullaged Savagnins (where the barrels are topped up with wine to prevent the oxidation process, ed.), he doesn’t seem to have lost an ounce of his enthusiasm, with any excesses managed by his wife and teammate of 30 years, Bénédicte. “Thankfully, we enjoy what we do!” he says, before heading off for the unmissable 9 o’clock coffee break with the rest of the team.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?