Exclusive interview with Lalou Bize-Leroy, Burgundy doyenne and wine legend: “Natural wine is complete nonsense”.

At 91, Marcelle Bize-Leroy, more commonly known as Lalou, from Domaine Leroy, is a force of nature. Standing at #5 in our rankings, we met her on her home turf in Auxey-Duresses.

The proud daughter of a winemaker father, Lalou Bize-Leroy founded her own négociant business and produced her first wines in 1955. Pioneering biodynamic viticulture in the rather conservative Burgundy region, she quickly gained a cult following, inspiring many of her peers both in France and across the globe. Cultivating an approach based more on instinct than on science, she sees her vines as living individuals, and likes to think that each wine is endowed with its own personality. Thanks to their unique resonance, her cuvées now reach stratospheric prices, particularly at auction.

Wife of the late Marcel Bize, who died in an accident in 2004, and co-manager of the legendary Domaine de la Romanée-Conti between 1974 and 1992 (in which she remains a shareholder), Lalou Bize-Leroy is wine royalty. It was an immense honour to meet her for an exclusive interview.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Lalou Bize-Leroy: I certainly don’t see myself as a champion, I’m an apprentice, somewhat studious, very studious actually. And every year I learn something.

Have you been training for long?

I tasted wine a lot from an early age; my father even brought wine to my lips when I was born. As a child, when I was supposed to be napping I would watch for the moment my parents left the lunch table to go into the drawing room, and I would sneak down into the dining room and finish their glasses. I’ve loved wine ever since I was a little girl, and I still do today. I must have been three or four years old, and it never did me any harm. I wanted to emulate my father, who told me from very early on that I had a good palate. I was as proud as a peacock, of course!

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

You have to respect the terroir, which of course means respecting the vine, cultivating it as it should be cultivated and not treating it like a cash cow. Small yields are essential. We average between 15 and 20 hl/ha here. Anything more can still be good, but I think 20 hl/ha is perfect. Vines are living creatures, no two years are ever the same, and each time it’s a different lesson that the wine – the vine’s offspring – teaches us. We try to do our best, and often we don’t do well enough.

You can always do better, if you take greater care. That said, there are years when we can’t do a thing. In 2004, for example, there were so many unripe grapes that we declassified everything into generic Bourgogne. That you have to be prepared to do, above all.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard? Biodynamics?

Biodynamics is a meaningless term. What people used to do was biodynamic, it just wasn’t called that. I was the first in Burgundy to talk about such things. Biodynamics involves taking the view that everything is alive and then respecting that life. We are, for example, all under the influence of the moon, and vines react in the same way as we do. As far as I’m concerned, I never cut them back, because I think it’s a massacre. Pruning a vine is just not right. It’s a plant – we’re not at the hairdresser – and these plants are being made to suffer like martyrs. Do people think I’m crazy? Well, yes, I am crazy. And the vines love me for it. They’re happy and look magnificent, with their tall canes. They’re free and content, without any stress. Cutting back is an abomination. I stopped doing it in 1988 because I couldn’t stand it anymore, it made me ill. The vines were happy straight away – or, at least, that’s how I understood it. I may have been wrong, but I don’t think so. Today, some people are starting to stop pruning, or to prune less.

And your most innovative strategy in the cellar?

You have to leave things to happen by themselves, keeping an eye on them, but, most importantly, not interfering constantly. I admire all those very specialist wine-making experts but, personally, I’m afraid of tinkering too much. If your cellar is too warm, then yes, you might think of intervening, as the wine needs to be just right, at exactly the right temperature. Our cellar is at a temperature of 12 to 14 degrees, with no draughts, as I don’t think the wine likes being blasted by cold air. Ultimately, of course, I have no idea, as I’ve never asked, but I don’t think it would feel sheltered or comfortable. I talk to my wines, I say “You’re beautiful!”, and to my vines, “You look beautiful!”, or “You look tired!”, or “Thank you.” You have to be present, to listen, look, smell, understand, and of course, taste. If the wine has a good, cool cellar, and is topped up – twice a week in our case, so that the barrel is very full and there is no oxidation – then the wine gets made, but we aren’t the ones who make it. It has everything it needs to be good, like all living things.

That’s something a “natural” winemaker might have said, so does this mean that you produce natural wine?

Natural wine is complete nonsense, of course it’s natural. If one lets the wine make itself, it won’t be any good. A wine still requires care.

Who is your mentor?

My father, for a start – an extraordinary man who allowed me to do everything. At the age of 23, he let me buy everything I wanted [for the estate]. He would always say, “She knows.”

Is wine a team sport?

You can’t make a wine on your own, it’s impossible – it’s a team effort. There may, however, be someone in charge. At my estate, things are mostly done according to my wishes, but I wouldn’t be able to do it on my own.

What is your favourite colour?

Blue. Ever since I was little. Yes, I am wearing blue today, I’m wearing it on purpose, even though my outfit isn’t all blue. I also like white.

Your favourite grape variety?

Pinot! I don’t know any other grape varieties. I was born with Pinot; we come from the same world. Other grape varieties, like Syrah, are almost different civilisations for me – but I’m not saying they are any less good.

Your favourite wine?

We have 26 wines on the estate [Domaine Leroy, ed.]. I like them all, as long as they have their own character. You have to make sure they retain their personalities at all costs. I prefer Saint-Vivant to Richebourg, for example. It’s not that I don’t like Richebourg, but my taste tends to lean towards something more refined. I prefer a Musigny to a great Chambertin, but there are some magnificent Chambertins!

Your favourite vintage?

1955! It was my first year, I’m sorry, but it’s still just as good. The ’55, ’59, ’61, ’64. I just love them.

If your wine were a person, who would it be?

The life of a wine mirrors the life of a person. I try to age my wines for a very long time. They are either male or female. They are, variously, babies, teenagers, and – fortunately – adults too! Here we are in 2023. This 1955 Mazis-Chambertin [in our glasses during the interview, ed.] is a youthful oldie with a lot to say. He’s an adult with a lot of experience. Only wine can tell you what the land is all about.

The vine is a true reflection of the person who grows it; it’s much more than just a plant. It’s like a person, it’s a living being. It needs a lot of care – it’s capricious and doesn’t let itself be managed like a herd of cows. It responds to our actions and wants to be loved. When I go to see my vines, I can feel how happy they are. They’re happy, and so am I.

What are the best circumstances in which to taste your wine?

Being open, being prepared to accept its message, as every wine has something to say. You mustn’t expect it to be a certain way. Just take it in!

With whom?

Never alone, because wine is for sharing. When I’m on my own, I don’t even feel like drinking wine. And you shouldn’t indulge in it every day.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wine?

Oh no, neither one of us needs it. Chaptalisation is not doping, it’s a form of support, and I’m not against it. If the weather is fine all year round, there’s no need for it. Sometimes you have to do it, it’s a fallback: if there’s not enough natural sugar, you have to add some.

To what do you owe your success?

There’s no such thing as success. There’s always room for improvement. We sometimes make progress, especially in understanding the terroir, the grapes, and I think we make a little more progress every year. That’s thanks to the vine, and it also depends on what the good Lord sends us. In short, I don’t think we should be complacent.

What is your greatest achievement?

I don’t have any, I’m not proud of anything because I have no reason to be. I’m never satisfied, as dramatic as that may sound, because I’m never very happy. I always have the impression that I haven’t gone as far as I should have. Wine is about striving to do better, but perfection doesn’t exist in this world. We’re happy as a family, I have a daughter who’s just lovely, and then I have my dogs.

If you’re not proud of yourself, are your dogs proud of you at least?

You’d have to ask them [Nine and Olga, ed.]. She [Nine, at our feet during the interview, ed.] is sleeping at the moment, but she loves me. I’ve always had dogs, often rescued ones. They arrive at my house – all I have to do is open the door and they’re there, it’s very handy!

Who is your most formidable opponent in Burgundy?

There are no opponents. There are only fellow winemakers who do their utmost, as I do, each in their own way.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

A lot of people, but I don’t know them. I go out very, very little and have a lot of work to do. I’m old, I don’t see anyone. As for my wines, there’s not a single bottle I’d be willing to part with.

Winemakers at the iconic Pomerol estate: “It’s easier to make great wines with strong women and sensitive men”.

Our next interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series finds us in Bordeaux’s Right Bank, where we meet Julie and Baptiste Guinaudeau, who stand at #6 in the rankings, a couple who create the kind of wines you fall in love with.

Just like its illustrious Pomerol neighbours, Petrus and Vieux Château Certain, Château Lafleur likes to keep its cards close to its chest. Julie and Baptiste Guinaudeau, partners in life and in wine, are at the head of this micro-estate of 4.58 hectares. Dynamic, engaging, and sociable, they are pursuing the work of Baptiste’s parents – Sylvie and Jacques Guinaudeau – who, in 1985, decided to take over the tenancy of Château Lafleur from two cousins, Marie and Thérèse Robin. In 2001, the Guinaudeau family acquired the entire estate. Baptiste and Julie, then aged 20 and 18, decided to take a leap of faith and move in. Twenty years later, this seems to have paid off: Château Lafleur is a cult name among professionals and collectors. Since buying their flagship estate, the Guinaudeau family has slowly built a constellation of different sites across the region, where they produce several wines: Les Perrières, Château Grand Village, and Les Champs Libres. These wines, more accessible than Château Lafleur, also showcase the skill and sincerity so characteristic of Baptiste and Julie’s work.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Julie Guinaudeau. – At the end of the day, this doesn’t really change anything.

Baptiste Guinaudeau. – What are we the champions of? Of nothing. We are, first and foremost, farmers; our lives follow the rhythm of the seasons. We are fortunate to be in this position and to be doing the work we love. Above all, we are very lucky.

Is wine a team sport?

BG: Yes, without a doubt. Wine is truly a team sport, one that isn’t bound by time or borders. Even more so in Bordeaux, contrary to the somewhat dusty, fossilised, “members’ club” image people have of it. In the wine world, Bordeaux is an exception. Nowhere else involves so many people who do not hail from the region and as many women in leadership roles. In fact, Bordeaux might be the region with the freshest and most feminine approach.

It’s important to stress that wine doesn’t encompass a single profession: there are several. We can’t do everything alone. For this reason, it’s essential to know who to surround ourselves with. We have an international, multidisciplinary team. Thanks to the renown of Bordeaux, we attract people from all around the world that want to work with us. We’ve never needed to post job offers anywhere. There are 25 of us in the team, of which a little under a third had never made wine before working with us. A third come from abroad, another third from other parts of France (most of whom had nothing to do with wine before joining us), and a final third from a more “classic” background. We really appreciate this group of people, who always give it their all.

Who is your mentor?

BG: Here, that would be me. You always need a conductor, a team coach, who has an overview of the game, but I discuss things with Julie and my parents a lot. We are a couple, following in the footsteps of another couple, Sylvie and Jacques (Guinandeau, Baptiste’s parents and previous estate managers, ed.) in the story of Lafleur. They are the ones who built the foundations of what we are today.

We have a specific progression path at Lafleur, and it always begins in the vineyard, for a cycle of two to three years. Out of 25 people, there’s only one person who’s never pruned a vine plant: our accountant! Other than that, everyone starts out in the vineyard with us. This is the foundation, the “core curriculum”. During those first few years, you get to know the true character of the person you have before you. This evolves: the team members mature, they change, and we constantly strive to get the best out of them.

Have you been training for long?

BG: We both began our careers in wine very young. We started working together 22 years ago: 2001 was our first joint vintage. What sets us apart is that we make wines together, as a couple. We are both in love with each other and with the wines we make. We are living on-site, 100% immersed, and are lucky to own the estate. We are among the youngest, but we already have two decades of foolishness and success behind us. My parents brought us into the fold from the get-go. Throughout the 2000s, the four of us worked symbiotically. We are a family that has been making wine for many years, but we’re only the second generation of full-time winemakers.

JG: I worked on my parents’ organic farm in the Lot-et-Garonne. I met Baptiste in high school when I was 16 years old. I came to Bordeaux to learn oenology – there was something magical about winemaking for me. I had the opportunity to make my first wine at Lafleur in 2001, which confirmed to me that it was something wonderful. I grew up with a strong sense of taste instilled in me, through my parents, who grew tomatoes and other vegetables. For this reason, I had a very developed palate. Wine naturally followed in the footsteps of my upbringing.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the team?

BG: Everything! We have a somewhat simplistic formula that states that great wine is the sum of three elements: a great soil (with a favourable climate); great genetics (when it comes to the variety); and a winemaker that calls the right shots at the right time.

To what do you owe your success?

BG: We owe it to discomfort, which is at the heart of our profession. As long as you feel discomfort, you’re not in any danger. It’s comfort that’s dangerous. Within prestigious, historic appellations, it’s being tempted to rest on your laurels. For us, discomfort came from having to buy Lafleur in 2001. When you buy land in Pomerol in the 21st century, it’s an investment, a gamble, one that needs to work out. The second discomfort came in the 2010s, when we had to change our distribution model because we weren’t reaching our consumers anymore. We looked for the best ambassadors, the best distributors, to share our vision with them. The latest thing that is stirring up discomfort is climate uncertainty, which we have always lived with, but which has turned a new corner today. What’s interesting is that we have never felt so much agency over it.

Are your daughters proud of you?

JG: They are, because they see how hard we work. There are few women in my profession and our daughters are proud to see me amongst other strong women in a male-dominated field.

BG: My daughters are proud of their mother. It’s easier to make great wines with strong women and sensitive men.

Who has been your biggest sponsor throughout your career?

BG: My parents.

Your favourite colour?

BG: All the reds.

JG: Yellow, because it’s the colour of the beautiful light we’re often blessed with in Bordeaux, that casts its warm glow on the landscape.

Your favourite variety?

BG: Bouchet. That’s what we call Cabernet Franc on the Right Bank. This fine variety fathered the two main Bordeaux varieties: Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. Born in the Basque Country, it was brought to Bordeaux by sailors, before ending up in the Loire Valley. It has everything going for it: grace, character, and a sense of balance that we love. As it’s relatively unknown, it always evolved in the shadows, and we identify with it. We live by the proverb “pour vivre heureux, vivons cachés” (“to live happily, live hidden”, ed.). Bouchet has been living on the Right Bank, in the shadow of Merlot.

Your favourite cuvée?

BG: The one we will discover next, whether that’s at home or somewhere else. I live in the future more so than in the past. At the moment, I really like the wines of Elian Da Ros – a winemaker from the same village that Julie grew up in, in the Côtes du Marmandais (in the Lot-et-Garonne, ed.). He is listed in Michelin-starred restaurants all over the world, but he marches to the beat of his own drum. His flagship wine is called Le Clos Baquet.

JG: The wines that have moved me the most have been German Rieslings. We’re very fond of the Prüm family, for example. If we had to pick one of our own cuvées, it would be Les Champs Libres. I love the idea that we can create something completely new with a Bordeaux variety (but with Liger-Sauternes genetics – Les Champs Libres is a Sauvignon Blanc from the Bordeaux Blanc appellation, but with a more Burgundian style. The first vintage was released in 2013, ed.).

Your favourite vintage?

BG: Always the next one to come!

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

BG: It would be Lafleur.

What’s the best way to enjoy it?

BG: Very simply and spontaneously.

JG: In a relaxed state.

With whom?

BG: With novice drinkers.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing your estate?

BG: We’re dangerous enough as it is! We don’t need to and neither does the wine. Great wines are pure wines, they don’t need any help to express themselves. We’re sometimes lucky enough to be able to go far back, and taste wines that are a century old. Even in that crude state, they are wonderful.

JG: We’ve tasted some incredible bottles. When we think about it technically, the conditions in which the wine was made, you realise the finest vintages were always the toughest, those where you managed, despite everything, to make a great wine.

For what price would you be prepared to sell your estate?

BG: It’s priceless. You would have to buy us alongside the estate, good luck with that!

Who is your most formidable opponent in Pomerol?

BG: We don’t have opponents. It might be because there’s less of a competitive spirit in Pomerol. You don’t have the weight of history, of rankings et cetera, unlike in other Bordeaux appellations, because our appellation is relatively young. We are tiny and we need each other. Together, we feel stronger. If we had an opponent, it would be the climate, but things aren’t black and white, because the climate can also help us. Just like a sailor fears the sea while depending on it, we fear and depend on the climate.

What is your greatest achievement?

JG: That Jacques and Sylvie placed their trust in me. They allowed me to express myself, to be a part of the family and hold the reigns, alongside Baptiste, of the production, in the vineyard and in the cellar. Others also saw my potential, such as Claude Berrouet (previously winemaker at Petrus, ed.), who taught us a lot. He educated our palates.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

To work and be in love! More seriously, we don’t innovate, because you must be wary of innovations in viticulture. Above all, you need to avoid being suddenly behind. You need to think long-term and take things slowly, but you also need to be able to act in the moment. We tinker, but we don’t innovate.

What’s your most original tactic?

BG: We harvest grapes that we’ve pruned. When we’re in the vineyard, we think about the wines we’ve enjoyed the previous day and discuss their various qualities. In the cellar, we always consider how we birthed the vintage, we think about the vines a lot. We spend a lot of time at the tasting table. We are against parcel-driven vinification. It can be very risky in tiny estates like Lafleur: micro-vinifying in the absence of mass. What makes the difference between a great wine and a good wine is the quality of the tannins, their length on the palate and the minutes that follow. The quality of tannins is linked to a delicate maceration. We prefer talking about “infusion” and “diffusion” rather than “extraction”. You need a minimum of mass for that, so these choices happen very early on. You can’t separate all the vines by age, by variety, by soil. 80% of the grape blend is made during the harvest.

JG: Wine is made in the vineyard. Once it passes the doors of the cellar, the die has already been cast. At Lafleur, it’s the sum of all the little details each step of the way, in the vineyard and in the cellar, that determine the end result.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

BG and JG: Our daughters!

New managers of the domaine: “Our dual leadership brings clarity and balance, allowing us to move forward more effectively.”

For the 43rd interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series, we return to Burgundy to meet Perrine Fenal and Bertrand de Villaine, who stand at #7 in the rankings. As leading figures in the region, they give us an insight into their passions, convictions, and savoir-faire in this exclusive first joint interview.

DRC. Three magic letters that any oenophile can instantly identify: Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, a legendary estate whose wines not only reach stratospheric prices at auction, but are also magnificently sumptuous and elegant, as if touched by a divine hand. This jewel of the Burgundy region, spearheaded for over fifty years by the iconic Aubert de Villaine and often considered to be the most prestigious estate in the world, is now run by Perrine Fenal and Bertrand de Villaine. Inspired by their illustrious predecessors, the two new guardians of the temple have achieved perfect harmony. Perrine Fenal, appointed co-manager in 2019 following the passing of her cousin Henri-Frédéric Roch, and Bertrand de Villaine, appointed in 2022 to take over from his uncle Aubert, represent the Leroy and the Gaudin de Villaine families respectively. The Gaudin de Villaine family has owned half of the estate since 1881; the Leroy family has controlled the other half since 1942. The new representatives emphasise the advantages of a historic system of joint management which, according to Bertrand de Villaine, “brings clarity and balance, allowing [them] to move forward more effectively”.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Bertrand De Villaine: We’ve never thought of ourselves as champions. What motivates us is not glory, it’s being out there in the vines.

Perrine Fenal: Our wines are the champions here.

Have you been training for long?

PF: I am self-trained, but I am lucky enough to have been born with winemaking heritage in my blood, soul, and heart, thanks to a grandfather, a mother, and a whole family of winemakers, whose know-how has been “infused” into me.

BDV: In contrast, I arrived on the scene later, some fifteen years ago now, and with a background more focused on international sales. I began training in the field from scratch, without the “infusion” that ran through Perrine’s veins. I wasn’t very closely involved with the estate when I was young. It all happened very slowly and steadily with my uncle (Aubert de Villaine, ed.). There was real training involved, both in terms of technique and passion.

How long have you been co-manager?

PF: Since 2019.

BDV: Since 2022.

Who is your mentor?

BDV: I started out in the vineyards with my uncle, and Henri Roch (the previous co-managers, ed.). And then, our estate workers were also my coaches, on a very practical level. Perrine and I are a real team: we coach each other and build our partnership every day. That’s the advantage of having two people, it brings clarity and balance, and allows us to move forward more effectively.

PF: In our family and within the estate, there have always been pairs of co-managers, sometimes with one less prominent than the other, but there has always been a representative from each family. I think that our way of working is quite special, it’s a real asset. At the moment, my coach is the life of the estate, our employees. Bertrand is also my coach. And we have Aubert, of course, as an inspiration, but he’s not a coach, he’s a sage. I also have my mother (Lalou Bize-Leroy, former co-manager, ed.) who, from afar, is also a presence and an inspiration.

Is wine a team sport?

BDV: We’re lucky to have such high-calibre employees. We learn a lot from them. We have a truly collaborative community that works very well, whether it’s from the vineyard to the cellar, or from the cellar to the vineyard, with us in the middle.

PF: Absolutely. We have all these essential jobs, all these people who are crucial to what each person does and to the final result, from the labourer to the person who packs the last bottle in the crate.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

PF: The terroir, without a doubt.

BDV: The terroir, and the respect that the winemaker has for the terroir, and therefore the winemaker too.

PF: It’s an osmosis between terroir and people.

BDV: If you don’t have the right terroir and the right vines on that land, and if you don’t have a good winemaker, you won’t make good wine.

To what do you owe your success?

PF: We are fortunate to have an exceptional terroir, which others before us have been able to identify, promote, and preserve. We have the immense privilege of holding it in our hands for a short while, and then passing it on to others.

BDV: Our real mission is to pass on and preserve the space that has been entrusted to us. Although there’s a title deed on a piece of paper, we don’t own this place: it’s a national asset, the legacy of a long history. This history is still very much with us, thanks to Saint-Vivant Abbey. Our greatest pleasure, our glory, will be to pass it on in as good a condition, if not better, than when we received it.

Is your family proud of you?

PF: Pride isn’t a word that’s used much in my house. Love, support, trust: these words have more value than pride.

BDV: We involved our two families, against their will, in this adventure. We work a lot, which creates constraints. I’m rather proud of them for accepting this. I hope that when our children see us working, they realise that it’s by working that we manage to have little comforts, little pleasures, and good times to share with others.

Your favourite sponsor?

PF: Lovers of our wines, who are moved when they open a bottle, quite apart from any question of price or snobbery, who rediscover the joy of celebrating a moment in life.

BDV: As Perrine says, the only thing that interests us is the emotion that our wine will bring out in a person or a group of people. Our best sponsors are the people who drink our wines.

What is your favourite colour?

PF: White, because it’s the sum of all the colours.

BDV: Blue, but it changes depending on my mood.

Your favourite grape variety?

BDV: A bit like us, it’s an inseparable pairing: Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Here, we have no choice when it comes to our appellations and, in any case, these two grape varieties have proven their worth over many years in Burgundy.

PF: I’m sticking with our good old Pinot, which stands up to whatever the weather throws at it. Its expressions are so varied that there are a multitude of sub-families that we will never tire of studying.

Your favourite wine?

BDV: I have a special bond, an affection, for Saint-Vivant, whatever the vintage. It’s often the Saint-Vivant that gives me my first thrills when tasting a new vintage, but I appreciate all our wines for what they are.

PF: For me, it’s often La Tâche. In 2022, it was incredible! A real hero.

BDV: Sometimes, with La Tâche, you have to wait 20 years for its full expression, but in 2022, we had a Tâche that welcomed you with open arms.

Your favourite vintage?

PF: I’m very sensitive to new things, like births for example. My favourite vintage is the one that has just come out of the fermentation vats to be put into barrels: the 2023.

BDV: It’s not my favourite vintage, but perhaps the most memorable: my first vinification in 2008, when I asked myself “What am I doing here?”. We had to throw away half the grapes, it was a terrible vintage. Perrine and I were lucky enough to taste a few 1971s, three different vintages that were quite similar to each other. I had the impression that I was almost more impressed than the people we had tasted them with. You open a bottle of wine that’s over 50 years old, and the quality is incredible.

If your wine were a person, who would it be?

PF: Its terroir. That’s what makes a wine a great success. It would be simplistic to compare a wine to a human figure.

BDV: Each of our wines has its own character. The Saint-Vivant is a very welcoming wine, like a maternal figure who takes you in her arms, who is strong and tender at the same time. Grands Échézeaux is a marathon runner, a wine that starts slowly and takes its time.

What are the best circumstances in which to taste your wine?

PF: Once again, it comes down to a question of mindfulness. Do you taste a wine to show your friends that you can afford it? That would be a shame. The best way is to let yourself be guided by your emotions, so that the emotion is there from start to finish.

BDV: With my old friends from before the estate. For some wines, I’m thinking in particular of the 1971s, you want to sit quietly in an armchair, in a moment of introspection, to drink them. Other wines are more suited to sharing; they bring an extra dose of conviviality.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wine?

PF: Yes, I often think of using vitamin C!

BDV: We improve our grapes by adapting the pruning system, but that’s maintenance and training, not chemical enhancement, to strengthen the vines and produce better quality grapes. We don’t use any chemicals; we’ve been biodynamic for years. We work more on plant cover, on microbial flora and on maintaining our soils, sometimes adding a little fresh compost. Nature does all the enhancement by itself, producing large quantities of grapes due to conditions that are optimal for growing fruit.

PF: Sugar is a drug, and the sun has given us vintages with a high sugar content in recent years!

Who is your most formidable opponent in Vosne-Romanée?

PF: The sky, and the weather (which is also our ally).

BDV: In 2021, for example, the weather was a fearsome adversary and it won the race. That said, it didn’t win entirely because we have some very fine wines in this vintage, but we just don’t have many of them!

PF: It forced us to give it our all, which is always good when you’re up against an opponent.

BDV: There’s a lot of fair play in this battle with nature, because it takes a lot, but it also gives us a lot.

Who is your most feared competitor?

PF: Competition is a good thing. What we fear most are the vagaries of the climate that could deprive us of vines for several years: an extremely severe frost, devastating hail, for example, or a ravaging fungus, such as flavescence dorée. We are in competition with ourselves, vintage after vintage, with our own wines.

BDV: We don’t take part in competitions, in the literal sense. We have no desire to compare our Échézeaux to another Échézeaux, or our Grands Échézeaux to another Grands Échézeaux. On the other hand, they are our mirrors, which can sometimes be our most formidable competitors!

And your greatest achievement?

PF: I don’t have much of an ego, so I don’t have much pride. Maybe it’s my long years of yoga! I am profoundly happy, have moments of joy, moments of sharing, but no pride.

BDV: For me, they’re my children, but it’s more a question of satisfaction than pride. I’m satisfied to see them progress in life, and to know that the team I form with Perrine is working well.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

PF: We don’t really know the word “innovative” around here!

BDV: It would be more a general feeling of never being still. In other words, winemaking is something that’s in a perpetual state of flux, and you have to be constantly on the lookout without becoming overly anxious. We stay open-minded, we observe, we try to make decisions that are reversible. As far as the vines are concerned, we’ve decided to opt for a pruning method that enables us to encourage the growth of wood and bring life to the vines, so as to ensure their longevity.

PF: We’re starting the third season with a more personalised pruning of each vine, with the aim of creating as little dead wood as possible and encouraging the flow of sap as much as possible. This requires a lot of work and time. You have to be very reactive, very aware of what’s happening at the right moment.

BDV: This approach is less invasive. We realise that the winemaker himself does a lot of damage to his own vineyard, leaving wounds and scars. And perhaps we could also add that we have to be careful with technology. It can sometimes provide solutions that run contrary to the idea we are defending. In other words, the vine must also fight naturally. We can help it by pruning, for example, to defend itself against the cold, but if we intervene too much, we run the risk of erasing all the properties that the terroirs bring to the wines and, by doing so, creating wines without personality, that don’t reflect their vintage and their cru.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

BDV: We know full well that we’re just passing through. We don’t know today who our successor will be, there is no chosen one, no pretender to the throne. It will be someone who seems to us to have the same thing at heart as we do: the privilege [of managing the estate] and the humility that it requires. Our real mission is to give this domaine back to others.

PF: Honestly, it doesn’t even matter whether it’s within our families or not.

Winemaker of the storied family-run estate: “Passion isn’t something you can pass down”.

Our next interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series finds us in the Northern Rhône, where we meet Jean-Louis Chave, who stands at #8 in the rankings, a winemaker perpetuating not only his family’s legacy but that of an entire region.

The sixteenth generation in a long line of winemakers, Jean-Louis Chave has proven to be a worthy successor. His wines, known for their precision and purity, express all the character of the Hermitage terroir. During the 1990s, the Rhône winemaker set himself a new goal: to reinvest in the Bachasson hillside, located in Saint-Joseph, the very place where the family’s ancestors began their viticultural journey. From the start of his career, Jean-Louis Chave turned to practices of days past to tend to his vineyard. Long before receiving the certification it holds today, the estate was already employing organic methods. However, the winemaker does not want to rest on the laurels of his success, in France and around the world, but remains on a relentless quest for perfection. Through this interview, we meet with a man of remarkable humility.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Jean-Louis Chave – This achievement is thanks to the terroirs that we represent, and we strive to live up to their standards. The winemaker is entirely reliant on the terroir – there is no great winemaker without great terroir.

Have you been training for long?

For us, it’s a family affair, as I’m a sixteenth-generation winemaker. This makes me think about the question of transmission, which I’ve often thought about and continue to think about now I have children.

What are we passing down?

You can pass down a profession, and all its ways of working, but passion isn’t something you can pass down. I started working in the vines in 1992 or 1993, it’s been 30 years now. This is a long-term commitment, the practice of winemaking. An athlete will try to repeat an achievement or try to improve on it in a short amount of time, but us winemakers, we need to wait a cycle, an entire year, to express ourselves again. Rather than speaking of training, I prefer to think of it in terms of interpreting the terroir. To really achieve this, you must understand it, and this takes time.

Who is your mentor?

My father, definitely. But also, the wine enthusiasts who follow our approach, to whom we have a sense of responsibility, a duty of excellence.

Is wine a team sport?

Yes, especially in our region, where the vineyards are planted on steep slopes, and are cultivated the same way my ancestors cultivated them, without any machinery. We think of ourselves as “gardener-winemakers”. You need one and a half people per hectare of vines, whereas, in other regions, one person can easily cover 12 to 15 hectares.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the team?

What counts is the terroir. The winemaker is just an interpreter. They mustn’t damage what Nature has given them; they are there to accompany the terroir to its fullest expression, which is the wine they will make from it.

To what do you owe your success?

To our good fortune in having certain terroirs that have been in our family for a very long time. We also owe it to our philosophy of a job well done, and to our craftsmanship that has developed over the years, always driven by the idea of continuous improvement.

Is your father proud of you? And your children?

With my father, I think the pride goes both ways, the satisfaction of seeing the story continue to unfold. As for my children, I don’t want to force them to be part of our story, of our profession. It needs to come from them. That’s another philosophy we’ve always embraced: that our story, no matter how long, can end, or transform itself. The Hermitage was here before us, and whatever happens, it will be here long after us.

Who has been your biggest sponsor throughout your career?

The world of wine enthusiasts, the people who encourage us in our work. Wine exists when it is enjoyed, when it conveys an emotion, a reaction. These emotions, these reactions, they encourage us to keep telling our story. Restaurateurs also play a very important role because they give life to our wines.

Your favourite colour?

The gradient of greens you find in the natural world, and the blue of the sky. As for wines, you can’t separate what you drink from what you eat, so the colour is going to depend on the dish. Ideally, you would pick a wine and adapt the dish to it. Unfortunately, we are living in a time where chefs receive a lot of media attention, which means wine often plays second fiddle.

Your favourite variety?

Our form of expression is Syrah for the reds, Marsanne and Rousanne for the whites. I can’t say I prefer Syrah to Marsanne, it’s like being asked to pick your favourite child. The variety matters little, what really matters is the terroir. The variety is the prism through which the terroir is expressed.

Your favourite cuvée?

Historically, at the estate, our favourite cuvées have been Hermitage wines. It’s my generation’s mission to give a certain importance to another appellation which is hard to define, but very captivating: Saint-Joseph. We are trying to raise the bar.

Your three favourite vintages?

I would say 1991, a vintage that has fully matured, and that embodies what a great wine of Hermitage should be.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

I would want it to be someone who resembles the terroir it hails from. When you make a wine, you think of its hills, of its landscapes. What I want is for people, when they taste our wine, to recognise a piece of its birthplace. For those who don’t know our terroirs, I hope they find the harmony, the softness, the strength, and the colours that characterise the great wines of Hermitage.

What’s the best way to enjoy it?

The best way to discover our wine is always with food, whether it’s at a restaurant, or sitting around a table at home.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing your estate?

What is chemical enhancement? Adding a bit of sugar, a bit of tartaric acid, the tannins brought by oak? What counts, is remaining true to yourself, and true to the wine. Wine must be natural, not in the sense that it’s free from additives, but in the sense that it must be true, sincere. It takes work, despite all this, to ensure wine is its truest expression, in relation to its origins and to what it should be. You can’t take a hands-off, laissez-faire approach, because without any intervention, wine would be vinegar! It’s a fine line: you must stay close to the purest of truths, but that isn’t going to happen automatically. At the estate, everything is organised so we can do as little as possible, but we sometimes need to accompany the wine so it can express itself fully.

For what price would you be prepared to sell your estate?

Everything is meant for the estate to remain in the family, but should that not be the case, we will probably sell, and this sale will be its own kind of transmission. It won’t be a question of price, because the most important question is knowing who will be taking on the estate and turning a new leaf in its story.

What is your greatest achievement?

The vine-covered slopes of Saint-Joseph, including one that belonged to my family from 1481 until the phylloxera epidemic in 1880. My ancestors worked on those steep slopes for almost 400 years and were forced to abandon them without really understanding what was happening. I’m proud of having been able to replant them, over 100 years later. They are located close to a town called Bachasson, next to a place known as Chave. I started this long-term project in 1995, and the last vines were replanted in 2007.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

My most innovative strategy has been working just as they did back in the day. When I first started, people would tell me: “You work like they did in the olden days.” At the time, what was groundbreaking was knowing all the names of the chemical molecules, or working with chemistry, whereas now, if you’re working with chemistry you’re stuck in the olden days! I’ve been interested in biodynamics for 15 years. I had counterparts and friends in other regions that followed biodynamic principles – Aubert de Villaine (previously co-manager of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, ed.) for example. I can’t explain why, but I feel like this method works.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

There is no hierarchy: it could be a young, passionate winemaker who does their job right, with a bright future. Every winemaker who does their job right deserves all the recognition they get.

Winemaker and manager of the French luxury house’s four estates: “One foot firmly on the ground, the other up in the stars”.

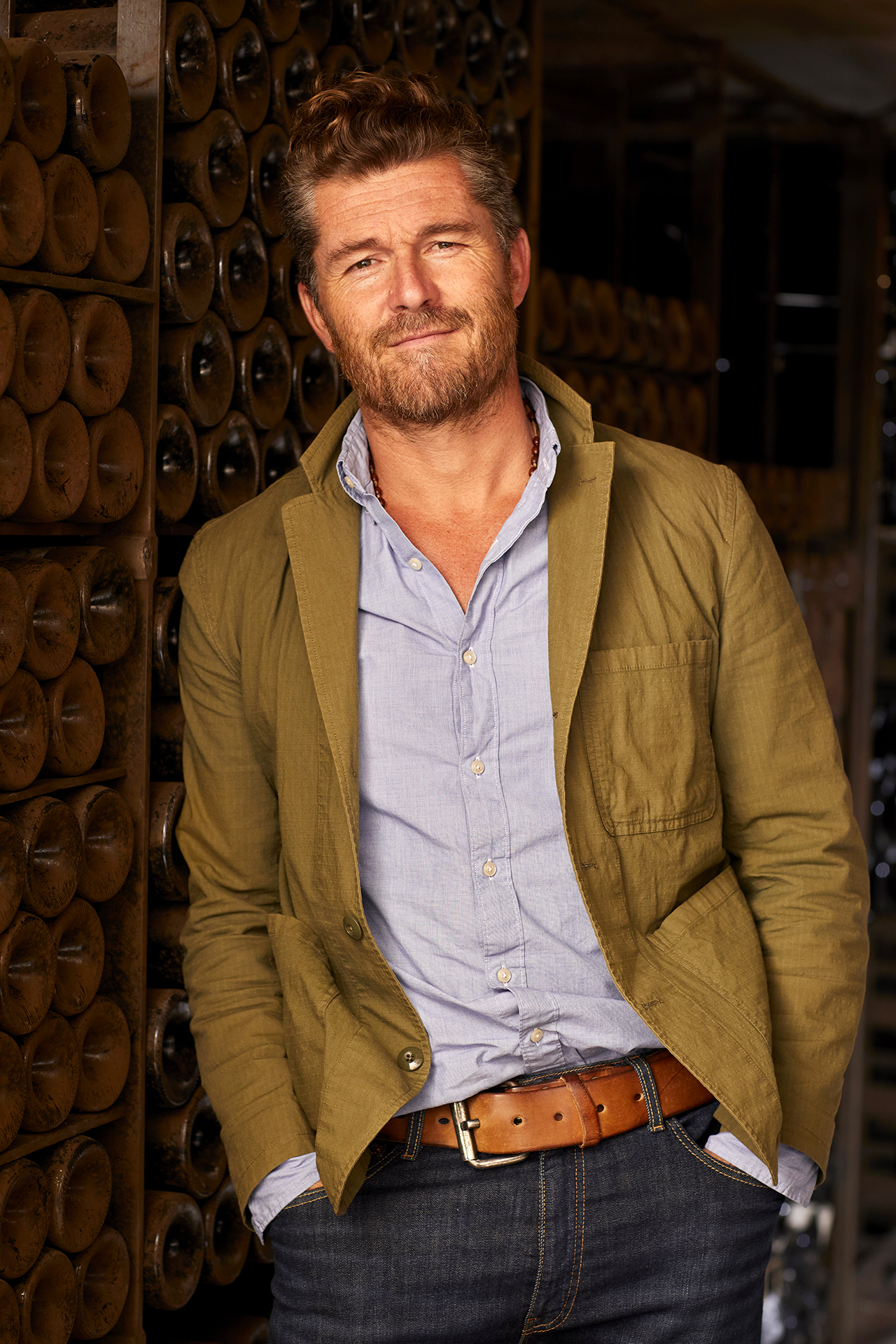

The iconic haute couture house has been producing wine for almost 30 years. At the head of Bordeaux’s Château Berliquet, Château Canon, Château Rauzan-Ségla, and Provence’s Domaine de l’Île, is Managing Director and globetrotter, Nicolas Audebert, who stands at #9 in the rankings.

Appointed head of Chanel’s vineyard properties in 2014, the talented Nicolas Audebert oversees three Bordeaux estates (Châteaux Canon and Berliquet in the Saint-Émilion appellation, Château Rauzan-Ségla in the Margaux appellation), and the Île de Porquerolles estate. With his casual appearance, tousled hair, and sun-kissed complexion, he exudes a rock-star charisma that has propelled him to magazine-cover stardom. The oenologist and agronomic engineer, who honed his skills at Krug before taking charge of winemaking at Cheval des Andes in Argentina, seems to possess the Midas touch, turning everything into gold. Whether it’s a classified Bordeaux Grand Cru or a Côtes de Provence rosé, this virtuoso of the vine knows how to craft excellent wine.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Nicolas Audebert: – I’m not even sure that I am a winemaking champion! I’ve been lucky enough to work for some very prestigious names that have helped me to get to where I am today. It’s the brands, the vineyards, the terroirs, and the people I’ve worked with that have brought me to where I am, a position where people might say that I’m some kind of champion, but really I’m not. There are scores of people who are far more competent than me. I take my hat off to all the small-scale winemakers who make fantastic wines for 15 euros a bottle, that nobody knows and who are the real champions, as their job is far more difficult. When you work for a big name, with substantial resources and great terroirs, it’s a whole lot easier.

Have you been training for long?

I don’t see it as training. I do it because it’s a real vocation: my love for grape growing and winemaking is behind everything I do. If we take the example of musicians or sports stars, there are those who achieve with hard graft, and then those who take real pleasure in it, who have a passion for it. Obviously, as winemakers, we’re constantly tasting things, and we probably taste other people’s wines more often than our own, to learn and understand. I’ve been making wine now for 25 years. I didn’t grow up in the wine world. I fell into it, I won’t say by accident, but because I loved nature and wanted to do something that involved being close to the land. Wine seemed an obvious choice: it allows you to transform an agricultural product into an experience that is emotional, sensory, cultural, historical. As winemakers, we have one foot firmly on the ground and the other up in the stars!

Who is your mentor?

We learn daily from everything – and everyone – around us. Whether it’s with a renowned South American oenologist, a Champagne cellar master, a wine connoisseur – I’m constantly discovering new things. I learn from talking to enthusiasts who’ve tasted everything under the sun, I learn from talking to winemakers who’ve been in the game decades. I was lucky enough to work with Rémi and Henri Krug for many years. I also worked with Maggie Henriquez, a rather exceptional woman, and with Philippe Coulon. I worked with Roberto de la Mota, the renowned oenologist from Argentina. I worked for 10 years with Pierre Lurton; he taught me a great deal. And I continue to learn every day with our estate workers.

Is wine a team sport?

Yes, it’s definitely a team sport. First of all, it’s a long-term process. Our team exists outside time – when we take a bottle of 1929 or 1947 Château Canon from the cellar, it’s the same team which made both wines. Great wines are not bound by the limits of time – they capture the essence of a particular place, a path, a destiny. We bear the weight of all that history on our shoulders; we need to write our own part in it.

There are many people in my team: first, the people who work every morning out in the vineyards. I’m not the one out there tending to the vines, pinching them back, tying them up, turning the barrels, racking the wine. After that, we have to blend and taste, with our consultant oenologists, Éric Boissenot and Thomas Duclos, and with our in-house winemakers. Beyond that, there’s also a little bit of Roberto de la Mota and Maggie Henriquez in my Saint-Émilion wines.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

Of those two elements, only one of them is indispensable: the terroir. If you don’t have an exceptional terroir or a distinctive winemaking signature, you won’t make good wine. That said, I don’t agree with the current line of thought saying that everything needs to happen by itself. Grapes that jump of their own accord into bottles and suddenly make great wines, without anyone doing anything, simply do not exist. You need someone to work on them, so it’s a union between the team that does that work and the terroir on which the grapes are grown – a bit like a horse and its jockey. It’s the horse that does the running, the winning, that has all the mental and physical qualities needed. But it needs a rider, to say “Go that way!” and to keep its pace steady at the beginning before sprinting to the finish line. That said, the ratio isn’t necessarily the same: it’s perhaps 80% horse and 20% jockey, whereas it’s probably 70% terroir and 30% winemaker.

If there’s nobody there to care for vines, and cut them back, they don’t make grapes, they just create tendrils and exhausted fruit. Without human hands giving them enough stress and direction, they won’t give anything. And without grapes, humans can’t make wine, so it really is the meeting of both, but a meeting where the winemaker’s style must be the expression of the terroir.

To what do you owe your success?

Above all, I owe it to my parents and to the upbringing they gave me. They taught me to be demanding of myself and of those around me, but they also imbued in me a respect for other people, a sense of patience, an ability to listen, boundless energy, and a desire to achieve, which means that I perhaps have certain qualities that make people want to go along with my projects and put their trust in me.

Is your family proud of you?

Yes, my family is proud of me. That said, the word “proud” sounds rather arrogant to me, a bit egocentric. I would like to think that the life that I am lucky enough to lead today – professional, social, and cultural – is something they look up to, rather than feeling pride for me. In my eyes, words like fulfilment, balance, and desire are far more important than pride.

Who is your most important sponsor?

If we’re talking in purely professional terms, it is Chanel. It’s a wonderful couture house which gives me the freedom to do what I do because it’s an organisation that understands you have to play a long game, and because it is run by people with a huge sense of creativity, who are striving for excellence. They are a truly extraordinary sponsor.

What is your favourite colour?

The colour of the soil, as it has so many different shades. There are ochre soils, red soils, brownish-black soils, sandy soils. It’s this mosaic of colours that allows us to make our great wines and bring complexity to them.

Your favourite grape variety?

I would have to say Malbec, as I hold a particular attachment both to the grape variety and to the wonderful country that is Argentina. It’s a grape variety with quite an extraordinary history, which ended up finding somewhere to call home on the other side of the world, in the most unlikely of places. It left Cahors and came to Bordeaux, where it was planted before disappearing again and going over to South America. It was planted first in Chile, then in Argentina; it crossed the Andes by horse, in the saddlebags of President Sarmiento and a French scientist called Pouget. And then, finally, it found a place in the foothills of the Andes, on the Argentine side, high up on the Altiplano plains, in a continental climate, where it felt at home and was happy.

Your favourite wine?

Amongst the wines that we have here in our cellars and that I have been lucky enough to taste, there are a few that are truly extraordinary, that mark you for life. There are certain vintages of Rauzan and Canon that I won’t ever forget, like 1964, 1955, and 1929, for example. They are all absolutely unbelievable wines. I have memories from all over the place, whether it’s in the Piedmont, in South America, in Burgundy, in Champagne. There are exceptional wines everywhere. However, if I had to keep just one bottle, the one that made the greatest impression on me, it would be Krug 1928, which has an incredible history. Bottles of this vintage had been seized by the Germans to be sold on the British market, but the British didn’t want them because they had been disgorged for a while, and Joseph Krug was able to salvage them. Bottles of Krug 1928 are almost 100 years old, and absolutely extraordinary.

Your favourite vintage?

I wouldn’t pick one that’s too old, or one that’s too young. I would have to say 2001 because, whether it was on the Right or the Left Bank, it made for an extraordinarily precise wine. It isn’t an iconic vintage by any means, but at the same time, it shouldn’t be overlooked. It’s not a small vintage, the wines it produced are very clear, very precise, they say what they have to say without shouting it from the rooftops, but rather with humility.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

My wines have a strong identity, they are the mirror of the land from which they were born. People often say that a dog is the reflection of its owner, but a wine must take after the place from which it comes. Today, you could make a wine in Margaux that was modern, sun-drenched, Mediterranean, extracted, powerful, with exotic accents – why not? But that is not what customers are looking for. Similarly, if you’re making, somewhere deep in South America, a wine without colour, that’s austere and cold – something is wrong. Wine reflects a culture, a path, and this path was set by the land, the climate, the people, and the wine needs to resemble this, it needs to be rooted in a very specific place. Take Canon for example, which has a very specific terroir, with clay-limestone soils, on the plateau of Saint-Émilion. This is a terroir that doesn’t lie, it’s a terroir where you couldn’t be doing anything else. When tasting a wine, people often make analogies to refer to its character. They often say: “This one is slightly withdrawn, it’s a little shy, you need to give it time. It needs to grow in confidence”. Or you could have a headstrong wine, that knows what it wants to say, and says it very bluntly and directly. I wouldn’t be able to make a wine if I didn’t have a clear idea of what kind of person it would be.

What are the best circumstances in which to taste your wine?

In good company. You should never drink alone, as wine is designed to be shared, to build bonds between people.

With whom?

Some people say that you should only open good bottles with people who understand wine, but I think that’s a real shame. In my eyes, you should open those bottles with anyone who wants to drink them, whether they understand or not. The pleasure, the sense of discovery, the satisfaction, and the emotion that great wines afford are within everyone’s grasp: those who know about them and those who don’t. Obviously, you shouldn’t open a great bottle with someone who won’t enjoy it, it wouldn’t make any sense. But if the desire to open it and share it is there, even the greatest bottle can be opened with someone who doesn’t know much about wines, because these moments are about conveying emotion, about passing on this immutable knowledge that exists outside of time.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wine?

I’m lucky enough – or unlucky enough – to be on a natural high all the time. I’d almost prefer for it not to be the case! However, I would never enhance my wine with chemical assistance. There’s this trend for souped-up wines but they bear no interest for me whatsoever. It’s far more interesting when things are full of surprises, when you gradually discover different aspects that bring complexity. This complexity is the opposite of in-your-face showiness. Chemically enhancing wines allows you to achieve a feat once but, behind that, there’s nothing, because it’s part of a system that is distorted from reality, showy, and short-lived. The point of wine is for it to be always true, and precise.

Who is your worst enemy?

I’m my own enemy – if I weren’t, life would be very dull! The hardest thing is to know yourself and to understand your own strengths and weaknesses. It’s always easy to talk about our strengths. Our weaknesses are much harder to work on. In the wine world, which is a world of pleasure, of shared experiences and emotions, I don’t really see any competition or enemies.

And your greatest achievement?

My only motivation is my family and our life together. I try to pass on to my children a bit of the upbringing that I received – with its values and traditions – but also an openness and willingness to discover the world. I still have so many things to do, places to go, wines to drink, countries to discover, people to meet: it’s this desire to be open to and interested in everything and everyone that I want to pass on to them.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

It is, above all, allowing ourselves to be innovative and not being scared of asking questions or implementing new things. In some places, the wine world is defined by a multitude of traditions; in others, it is all about constant innovation. It is quite rare for the two things to coincide. In the places where it’s very traditional, if you do things a bit differently, then it’s often very marginally so, just to be able to say that you do things differently. On the other hand, there are some vineyards, some regions, that aren’t bound by tradition, and are free to innovate. In a traditional vineyard, wanting to do things differently is ultra-modern and innovative in and of itself. When I arrived in Bordeaux, I had never worked in the region before. I had no qualms about implementing new ideas or developing things that didn’t follow the traditional Bordeaux way. You need a mix of both: one eye looking ahead and one eye looking back.

Can you give me an example?

Conducting several harvests within the same plot, for example, according to the exposure of the rows, and then vinifying the grapes separately according to this. Depending on the aspect of the row, some phases get more sunlight than others in the very warm years, with grapes that will be riper, spicier, darker, and more intense than others that will be fresher, more acidic, and have more tension. It’s hard to vinify them all together while staying precise, so in certain years we do several harvests within the same plot and vinify its grapes separately. Another example is the concept of having people taste wines straight from the barrel during en primeur and for the definitive blend, letting them can pick whatever barrel they want to taste from, which allows us to talk about the wine and be completely transparent about what we have in our cellars. There is a highly distinctive approach to tasting in Bordeaux.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

Pierre Lurton. One should always pay honour where honour is due!

Burgandy’s talented winemaker: “I juice myself up on Pinot Noir”.

For the 40th interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series, we return to the Morey-Saint-Denis to meet Jacques Devauges, who stands at #10 in the rankings. A staunch supporter of the Côte-de-Nuits, he is an advocate of excellence. From one estate to the next, he continues to pursue the same goal: expressing the nobility of the Morey-Saint-Denis terroir.

The former manager of Clos de Tart between 2015 and early 2019, Jacques Devauges joined Domaine des Lambrays that same year, moving from an estate owned by François Pinault to one owned by Bernard Arnault. It was “chance and a series of encounters”, he explains, that brought him to where he is today. Although nothing predestined him for the world of winemaking, he fell in love with it during a harvest season, with his baccalauréat in hand, at a small estate in Pommard. “After that, I met some intelligent people who put their trust in me”, he says with humility. Today, as head of Domaine des Lambrays, a leading Côte-de-Nuits estate, he intends to continue the work of his predecessors, while instilling a new energy and uniting a team around his most deeply held principles. Here, we talk to a modest man who listens attentively to his terroir.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

I distance myself a lot from these things. I’m incredibly lucky to be doing a job that I’m passionate about. When you get up in the morning and love what you do, everything is easy. So, I don’t see myself as a champion. The Arnault family trusts me and has handed me the opportunity to work with some extraordinary plots.

Have you been training for long?

I chose to work in the field. I have a degree in oenology, of course, but I started from the ground up.

Who is your mentor?

I didn’t really have one mentor in particular. I met Denis Mortet, a winemaker from Morey-Saint-Denis, who helped me a lot when I didn’t know anyone, then Christian Seely, the President of Axa Millésimes, who gave me the keys to the Domaine de l’Arlot, and finally Sylvain Pitiot, who I consider to be one of the greatest Burgundian winemakers, as much for his professionalism as for his warm personality.

Is wine a team sport?

Completely. You can’t do anything on your own. Before we talk about the wine, we talk about the vine. The sense of team spirit is strong because it’s rooted in time. It’s not just a horizontal team but also a vertical one, across the generations, and that’s what I find so powerful about our profession. It’s a real pleasure to come into a field and get your teams motivated by a project. You can’t have a vision on your own. You have to get everyone on board, not just the team, but your customers too.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the winemaker?

The terroir of course. It’s a bit of a cliché, but you need a great winemaker to make a great wine, it’s a symbiotic relationship. The climate is just as important as the soil and the work of the winemaker. All these elements have to be present for a wine to inspire emotion. That’s not to say that you should only drink grands crus costing thousands of euros. Emotion is the alchemy of a whole range of elements. That’s why wine is so fascinating.

To what do you owe your success?

I see myself as a student. Every year brings a new challenge, and you have to try new things, so I can’t explain my success, because I learn something new every year. This desire to adapt and observe is essential. You must remain humble and curious, and strive to produce pure, precise, clean wines that fully reflect the place from which they come.

Is your family proud of you?

My mother is, and always has been – that’s a mother’s role.

What is your favourite colour?

A very distinctive colour, that of very old Burgundies from the 1920s and 1930s, up to 1940. Pale in intensity, with a pinkish transparency and hints of faded pink, it could almost be a shade of tea. In a nutshell, somewhere between aged pink and tea. These are moments you remember for the rest of your life. Wine is also about working with the generations that came before us, and this colour is there to remind us of that. These are wines of impressive power.

Your favourite grape variety?

I’m a big fan of Pinot Noir, which is what moves me the most, but I also like Gamay grown on granite soils, and Syrah from the Northern Rhône.

Your favourite wine?

Clos des Lambrays has a fascinating terroir, something that everyone can see when they walk through the vines. There’s an extraordinary diversity that can be found in the wines, which have a very elegant mouthfeel. It’s because of this parallel with the landscape that I love it so much. Long before I arrived at the domaine in 2002, I tasted a Clos des Lambrays 1918, and it still impresses me now as it did then.

Your favourite vintage?

I like fragile, complicated vintages, which you can feel when you taste them. Decades later, they’re still standing. I’m reminded of 1918 or 1938, which are forgotten years, with a historic dimension.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

No idea, I don’t think it’s for me to say. Each one has its own identity, and I like to think that the identity of each wine is linked to the soil. We produce nine different wines, each with its own personality.

What are the best circumstances in which to taste your wine?

Whenever the mood strikes; it’s the opportunity that creates the greatest tasting moments. Sometimes a friend or family member drops by, and you’re drawn to one bottle rather than another. Those are the best moments. For our wines, you have to open them three hours in advance, without putting the cork back in.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing yourself, or your wine?

I juice myself up on Pinot Noir. But at the estate, we have this ideal of purity, which means using as few inputs as possible.

Who is your most feared competitor?

The hazards of nature, which are extremely frustrating. No matter how hard we work, when Nature decides otherwise, she’s always right. Every vintage has its difficulties, to a greater or lesser extent, but we try to turn them into strengths. In 2021 for example, Nature was unkind, but a few years later, I’m delighted with this vintage, which I didn’t see coming, with the grace, elegance, and delicacy that we’ve come to expect from the climate. If you’re clever enough, you can make a friend out of it.

And your greatest achievement?

To see that my team at the estate is supporting me in this project. We went organic, then biodynamic, and it makes me proud to have a whole team who wasn’t in that frame of mind before, and who now couldn’t go back. And the customers, who are rediscovering Clos des Lambrays. These are the two driving forces behind our passion.

What has been your most innovative strategy in the vineyard and in the cellar?

At the estate, we renovated our facilities in 2022, which took us two years to complete. We developed a gravity system, which is very simple: in the centre of the building, we have two vats that go up and down, and the wine flows very naturally. We have developed unique wooden vats, ones that are not truncated. We’ve had cylindrical vats developed, which allow us to use a movable ceiling that forms a watertight seal, enabling us to keep our bunches whole before fermentation starts. This system allows us to avoid using acetate and to vinify in oak.

Who would be your ideal successor on the podium?

I’d like to find someone who thinks differently from me, not about the fundamentals, but about how to get to them. Someone who takes this estate, these terroirs, and this domaine head on and finds their own way to express it.

Winemaker of the family-run estate: “We have never compromised”

Our next interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series takes us to Morey-Saint-Denis, in Burgundy, where we meet Christophe Perrot-Minot, #12, who continues to forge his own path and ruffle a few feathers along the way.

The former courtier, forever championing the expression of the terroir, and whose knowledge of viticultural regions informs the expertise of his Burgundian know-how, refuses to forsake perfection in the pursuit of profitability. The winemaker, aware of the allure of Burgundy’s Grand Crus, is driven, above all, by the desire to express the taste of his vineyard – a powerful voice, both refined and gracefully tannic, which impels you to listen. To hear it, nothing must be overlooked. Although the estate sources grapes from various plots across the Côte-de-Nuits, Christophe Perrot-Minot supervises every harvest, carried out by his own team, be it in Gevrey-Chambertin or Clos de Vougeot. Organically certified for the past few years, Domaine Perrot- Minot belongs to one of the most sought-after appellations, an appellation that is facing necessary changes to preserve its nature. This challenge – to reveal what the land does not give you outright – is one the winemaker takes up with gusto.

Le Figaro Vin: How does it feel to be crowned a winemaking champion?

Christophe Perrot-Minot – I really don’t consider myself to be a winemaking champion, it’s not something I’ve ever thought about.

Have you been training for long?

I’ve been training for over 30 years. I arrived at the estate in 1933 and before that, I had played at being a wine broker for seven years. This gave me a great overview of what everyone was doing: I could walk into a cellar one morning and meet someone who was struggling to solve a certain problem; a few hours later I would walk into a second cellar where a different person had faced the same issue and solved it years prior. Just like that, I would bring the solution back to that first person. This helped me take a step back and gain perspective on this profession. That experience was the intellectual key, the key to realising what I wanted to be doing, the key to achieving the result I had in mind, to obtain the style of wines that I wanted.

Who is your mentor?

My only mentors have been observation and reflection, because at the end of the day, I have never collaborated or vinified with my father. When I joined the estate in 1993, he handed the reigns over to me. For everything related to vinification, I had a pretty clear vision of what had to be done and avoided, a vision that was in opposition to the previous generation’s, who cared more about production. This had a lot to do with the education of the time. When I first arrived, I had ideas that went against those of my father in terms of lower yields, of sorting – all these things were very hard to accept for that generation. They had been told, in the 1980s, that you needed to plant productive clones. There was a time when Burgundy was more focussed on quantity than quality. We had to fight to switch gears and convince people, for example, to throw out grapes. Things didn’t change in a year! As for the sorting, we implemented it as soon as I started, but accepting this practice took much longer.

Is wine a team sport?

Wine is a team sport. Everyone needs to understand what direction we’re going in and accept it. You also need to surround yourself with competent people. You can’t make wine, let alone good wine, without a team. A winemaker can’t do everything themselves. You mustn’t forget that it takes many hands to craft a wine. All those hands, put together, give the grapes their potential. And this before even mentioning their provenance, the terroir… I also know that my opinion needs to be contradictory, and I have a right-hand man at the estate with whom I talk about different options regarding the bottling, harvest dates, and many other parameters. I think you move forward more efficiently when you can eliminate any doubt or hesitation. For me, the key to success is having a competent team you can exchange ideas with in order to move forward. I often like to say that they would be nothing without me, and I, nothing without them.

What is the key to making a good wine? The terroir or the team?

It’s always easier to make a great wine with a good terroir. But in a team, everyone is moving in the same direction, and you can express the terroir with even greater quality.

To whom do you owe your success?

I think the estate’s success is linked to the people that work there, and to our relentless pursuit of quality. That is, we prioritise the intrinsic quality of the grapes during vinification. We don’t think about the bottom line when we’re sorting them, or that we’re getting rid of “Grand Cru” grapes. We don’t calculate how much we’re losing when we discard some of them. No. We have a clear vision that is entirely based on the grapes’ intrinsic quality, without worrying about the appellation. I think for us, there is a lot of discipline and very little compromise – perhaps no comprise at all – on how the grapes that enter our vats need to be.

Who has been your biggest sponsor throughout your career?

Our best sponsor has been consistency. By which, I mean that we have never compromised. Whatever the vintage, we have always managed to keep the best grapes. “Whatever the cost”, as our president would say (a political doctrine coined by French president Emmanuel Macron during the Covid-19 outbreak, ed.). Whether we’re sorting Burgundy, Morey, or Chambertin plots, the process will always be the same. Why? Because I think all wines reflect an estate, its ambitions, its absolute character, and that of the people who work there. So, this refusal to compromise is a form of self-respect, and of respect for our clients. Moreover, everyone knows that Burgundy wines are expensive, but you mustn’t forget that there are people willing to pay €30 or €40 for a bottle of Burgundy – and I’m talking about the Burgundy appellation – which is a fortune. This might be the most they spend on a bottle in a year. And that’s why the estate’s most affordable bottle must be faultless. This is what I think.

Your favourite colour?

Red. In all its different shades. You can find a lot of different personalities in reds.

Your favourite cuvée?

The Mazoyères-Chambertin. Because it’s an appellation that I’m in the process of reviving. Everyone knows that when you’re making Mazoyères-Chambertin, you can call it Charmes-Chambertin. For marketing reasons, or for ease, it’s sold under the name Charmes-Chambertin. When in reality it has a completely distinct personality from Charmes-Chambertin, and it deserves to exist independently.

Your three favourite vintages?

The 1993, because it was my first. The 2003, because it was my first time vinifying an extremely hot harvest. After that, I would say the one that followed.

If your wine was a person, who would it be?

It would be the people that made it.

In that case, would it be you?

Even though it’s the product of teamwork, the style is personal. My team is so committed, that they will work to achieve the style that I want to see, that I’m looking for. My desired style is balanced, elegant, and refined wines. With tannins that are integrated, silky. Wines that, I would say, can be good regardless of time. I always think of Henri Jayer (a French producer credited with introducing important innovations to Burgundian winemaking, ed.), who used to tell me: “Christophe, a good young wine makes a good aged wine” and “a good wine needs to be good at all times”. It was so simple yet so true.

Have you ever thought about chemically enhancing your estate?

What really led to a change in quality, beyond the work and everything we have done these past 10 years, was our organic conversion, despite being long overdue. With this organic conversion, we noticed how the wines became more transparent and luminous. The juice became much more precise. And this increased the quality massively.

For what price would you be prepared to sell your estate?

You can’t sell something you’re only renting, so it is not for sale.

France’s 13th best winemaker: “I love drinking fine wines with people who know nothing about them”.

The mere mention of the name of this Grand Cru Classé is enough to send wine-lovers into a frenzy, and even those who have never had the chance to taste it agree that this is a Château destined to go down in history.

For the 38th interview in Le Figaro Vin’s series, we return to the border between Pomerol and Saint-Émilion, and Château Cheval Blanc, which is owned by the LVMH group and the Frère family. In July 2023, Pierre Lurton was appointed President of the Management Board, while Pierre-Olivier Clouet was promoted to Managing Director – arguably one of the most globally envied positions in the Bordelais appellations. Clouet, who describes himself as “incorrigibly hyperactive”, joined the estate as an apprentice but rose through the ranks with the elegance of a cat, gradually gaining the trust of Pierre, his mentor and great friend, who conferred on him the role of technical director at the age of 28. As well as his charm and extraordinary capacity for work, the fact that he did not come from a wine background was a considerable advantage for the young Norman, who very early on dared to “say out loud what others were thinking”. He is a free and rebellious spirit wrapped up in the demeanour of a gentleman farmer and bears a humility that allows him to assert his ideas with great ease.

“When I think about it, it was surreal”, he recalls with a burst of laughter. “At first, the suit seemed much too big for me”. The future proved him wrong, and it was alongside a close-knit team that he succeeded, one by one, in meeting the challenges posed to an estate that had to demonstrate its modernity without ever denying its roots. Creating a white wine from scratch, opting for agroforestry, finding plots of land at the foot of the Andes – all of these challenges have been overcome thanks to “the stability that Pierre has been able to give me for many years, which has allowed me to see each of our developments through in the long-term”.

Le Figaro Vin – How does it feel to be crowned a wine-making champion?

As always, I wonder why I was chosen! It’s something I’m very proud of, and I’m delighted that people come looking for me. 15 years ago, I was a nobody, and I never had a career plan. I feel both very grateful and infinitely small.

Have you been training for long?